Before we dive into today’s topic, let’s talk about two of my favourite words: Flotsam and Jetsam. I just love the way they sound! The way I understand them, the difference between the two is intention: Flotsam are things unintentionally donated to the sea – things washed overboard from a ship, or things blown off land by a storm. Jetsam is rather something intentionally jettisoned – if a ship needs to lighten its load to avoid sinking, for instance; in the case of the great garbage patches, it is a mixture of both: Without proper disposal systems in place, such as municipal garbage disposal, or education in ecological footprints, social debris is simply tossed and forgotten. But it ends up somewhere, often finding its way to the ocean through rivers and streams. And this leads us to the topic of ocean currents.

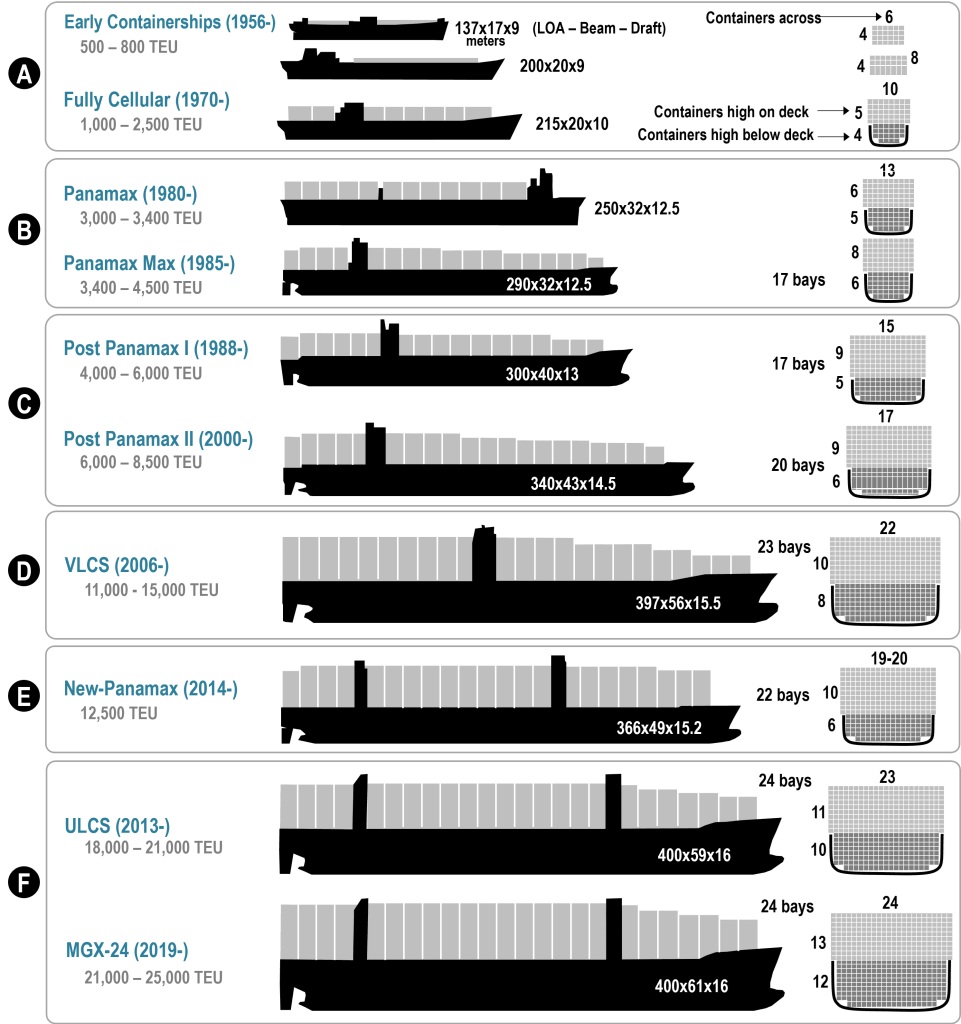

Today’s topic is a fascinating dive into a world of global trade; research has shown that around 90% of international trade is carried by shipping containers, and the World Bank statistics show that in 2019, nearly 800 million were shipped annually; given the increase over the past few years in online shopping, I can imagine that figure is by now significantly higher. The unit used for measuring how much a ship can carry is TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit); the chart below shows the adaptation of ship sizes over the years, driven by global trade:

Now, imagine a shipping container stacked at the top of a pile that’s the height of the actual ship; add to that ocean swells and waves. I’ve been on ships in the Atlantic facing waves so high, I could count fish through my window. I’ve been on ships in the “Sailor’s Nightmare” – the Pentland Firth passage between Scotland and the Orkney Islands – which is characterised by rough bathymetry (the underwater equivalent to topography) and extremely high currents (which also ricochet and collide off of the coasts of the islands and Scottish cliffs), tossing anything on the surface like a leaf in the wind. The World Shipping Council estimates that, over the past 16 years, an average of 1,500 containers have been lost at sea annually. Every year, the contents of those containers are carried along until the container is breached by either corrosion or impact. Then the contents are carried by ocean currents; where they finally make landfall depends on where they entered the ocean. If you were marooned on an island and tossed out an SOS in a bottle, it could make landfall anywhere between two and one hundred years – or never, if it’s caught in a gyre (more on that later). A message in a bottle was found on a beach in Norway that had been sent off 101 years earlier.

So what does that have to do with rubber ducks? In 1992, a shipping container with a consignment of what has been dubbed Friendly Floatees – 28,800 yellow rubber ducks, red beavers, blue turtles and green frogs – was washed overboard (along with 11 other containers) into the Atlantic. Because they are designed to float on water, they have survived at sea for an amazingly long time. Seattle oceanographers Curtis Ebbesmeyer and James Ingraham, who were working on an ocean current model, OSCUR (Ocean Surface Currents Simulation), began to track their progress; and those wee toys went on all kinds of adventures: Ten months after they broke free, some began showing up along the Alaskan coast; some showed up in Hawaii; some went to see the site of the Titanic sinking before getting frozen into ice, eventually emerging again and travelling to the US eastern coast, Britain and Ireland, making landfall around 2007. The researchers contacted coastal regions, asking beachcombers to report their finds; they recorded findings and began to accurately predict where landfall would occur. Over the years, the ducks and beavers had faded to white, but the blues and greens had retained their colours.

Flotsam and Jetsam have played key roles in helping researchers understand not only how ocean currents travel, but also how the areas known as garbage patches, oceanic gyres, are formed and retained by the swirl of ocean currents. Currently, five patches are known; many of the rubber ducks are likely caught in such currents, so we may hear about more white ducks finding their way to beaches in the coming years.

So the next time you see a rubber duck, think of all the adventures its siblings have been on!

If you’d like to see for yourself how ocean currents work, click here for an interactive map; just click on any area of the map to see how and where the currents carry debris from that point.