For those outside of the US and/or Millennials, the term “Burma-Shave” might be new to you – which is why I’d like to “undust” this fascinating little piece of history.

The 1920s was a time of change; World War 1 was over, and the following Spanish flu had wiped out more people than the war itself; the survivors just wanted to celebrate life. Out went the starchy mentality of Victorian dresses and in came the flappers; innovations and scientific breakthroughs fed the hunger for the new and anything that made life easier.

At the time, men shaved themselves with shaving cream applied to the face with a brush and a straight razor blade (still common into the 1950s, when the double-edged safety razor began to gradually take over).

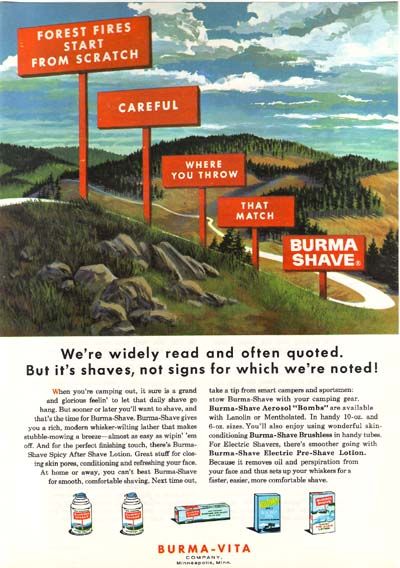

Enter, the Burma-shave brushless shaving cream: Introduced in 1925 by the Burma-Vita Company in Minneapolis, Minnesota, it was purported to have come from “the Malay Peninsula and Burma.” It was, in fact, a result of chemical experiments by chemist Carl Noren. The monicker was a marketing gimmick, much like products touting to be “Swiss” that are unknown here (even “Swiss cheese” – which one of the hundreds is meant?). The cream didn’t really take off, and while other similar products were coming out of larger companies such as Barbasol and Gilette, Burma-Shave managed to beat the odds when their clever advertising campaign was hit upon.

Around this time, the Ford Model T had become a huge success, with millions of new automobiles on ever-expanding road systems. Roadside signage was taking off, and the advertising gimmick was destined to go down in history as one of the quirkiest success stories.

Burma-Shave ads were a series of signs along the road that concluded in the sign saying “Burma-Shave”. The first couple of years, the signs were rather prosaic ads for the company; but as they began bringing in repeat customers, the signs became bolder and more experimental. They became more humorous rhymes – usually five signs, with a sixth ending the series as “Burma-Shave”.

Here are a few examples:

- Shaving brushes / you’ll soon see ’em / on the shelf / in some / museum / Burma-Shave (1943)

- Uncle Rube / buys tube / one week / looks sleek / like sheik / Burma-Shave (1930)

- A shave / that’s real / no cuts to heal / a soothing / velvet after-feel / Burma-Shave (1932)

- Shaving brush / and soapy smear / went out of / style with / hoops my dear / Burma-Shave (1936)

- The Burma girls / in Mandalay / dunk bearded lovers / in the bay / who don’t use / Burma-Shave (1937)

As cars began to speed up, safety messages increased around 1939:

- Hardly a driver / Is now alive / Who passed / On hills / At 75 / Burma-Shave (1939)

- If you dislike / big traffic fines / slow down / ‘till you / can read these signs / Burma-Shave (1939)

- At crossroads / don’t just / trust to luck / the other car / may be a truck / Burma-Shave (1939)

- Don’t pass cars / on curve or hill / if the cops / don’t get you / morticians will / Burma-Shave (1940)

- At intersections / look each way / a harp sounds nice / but it’s / hard to play / Burma-Shave (1941)

When World War 2 came around, the signs reflected the social conscience:

- Maybe you can’t / shoulder a gun / but you can shoulder / the cost of one / buy defence bonds / Burma-Shave (1942)

- Shaving brush / in army pack / was straw that broke / the rookie’s back / use brushless / Burma-Shave (1942)

- Slap / the Jap / with / iron / scrap / Burma-Shave (1943)

- Tho tough / and rough / from wind and wave / your cheek grows sleek / with / Burma-Shave (1943)

A few humorous signs:

- She kissed / the hairbrush / by mistake / she thought it was / her husband Jake / Burma-Shave (1941)

- We know / how much / you love that gal / but use both hands / for driving pal / Burma-Shave (1947)

- I use it too / the bald man said / it keeps my chin / just like / my head / Burma-Shave (1947)

- Road was slippery / curve was sharp / white robe, halo / wings and harp / Burma-Shave (1948)

- If you think / she likes / your bristles / walk bare-footed / through some thistles / Burma-Shave (1948)

- A man / a miss / a car – a curve / he kissed the miss / and missed the curve / Burma-Shave (1948)

- Our fortune / is your / shaven face / it’s our best / advertising space / Burma-Shave (1963)

Toward the latter part of the signage, they began recycling earlier messages. Road signs and maintenance became increasingly expensive, and cars sped by faster than ever. The signs disappeared from the roads in 1963 when the company was sold to Phillip Morris and they discontinued the marketing campaign, which turned out to be a mistake; sold once again, the product eventually disappeared, but the term “Burma-Shave” can still be heard, referring to short, quirky rhymes.

To read more about this topic:

Route Magazine: Defining the American Dream, One Sign at a Time

I hate to end / this fun article / but time is short / so here’s what’s possible / Burma-Shave examples from Pinterest:

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.