I’ve been thinking about writing on the topic of the Radium Girls for some time now. In our home library, the book by Kate Moore, The Radium Girls – The Dark Story of America’s Shining Women (2017), has been glowing at me (not literally, thank goodness!). The book is a fascinating history of the women who worked in watch-making factories across the States, and the groundbreaking battle for workers’ and women’s rights, which helped shape labour laws that would protect future generations from shameless exploitation.

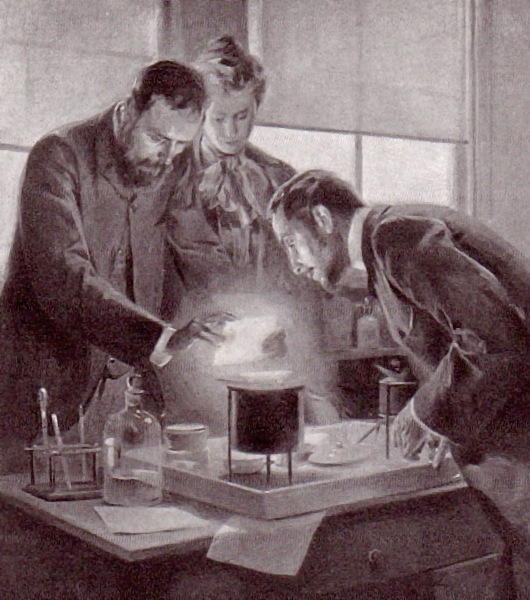

Curie is the unit of measurement for radioactivity, named for both Marie Sklodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie (co-winners of her first Nobel Prize, in Physics, 1903); Marie went on to win a second in another field (Chemistry, 1911). Their oldest daughter, Irene Joilet-Curie, won the Nobel Prize (with her husband, Frédéric) in 1935, also in chemistry. Marie Curie died from the effects of exposure to radiation on 4 July 1934 (her husband would have had the same fate, but he was killed in 1906 in a road accident). Even today, her papers and even her cookbook are so radioactive that they are stored in lead boxes, and anyone examining them must be fully protected. I could do a whole history of the Sklodowska and Curie families; the women were intelligent, educated, ahead of their time and left their marks on history in several fields of science. [I don’t know if the book would be available where you live, but the youngest daughter of Marie, Eve Curie, wrote a biography about her mother, published in 1937 in several languages (I have the 1938 Swiss edition, in German). The book can be found in e-book formats as well.]

Radium, discovered by the Curies in December 1898, caught public fascination; soon, Radium was touted as the cure-all of the new century. It was sold as healthy, as something that would make your skin glow. It was said to cure ailments and recharge your physiological batteries with pure energy. It was put into toothpastes, face creams, soaps, bath salts, makeup, and pure energy drinks. And it was painted onto the face of watches: Each painter would mix her own paints in a small crucible; they each had a camel hair paint brush and were instructed to keep their brushes pointed with their lips: Lip, dip, paint. The girls at the factories would paint their nails and faces with the paint for fun.

And then people started getting sick. Eaten from the inside out, their bodies started disintegrating, and they started dying. And at the time, workers at factories were earning a penny per watch face painted; they were too poor to quit, and too sick to work. And the company big boys denied all responsibility, medical aid or financial compensation. Eventually, though some of the Radium Girls tried to sue the United States Radium Corporation, the company dragged the case on so long that most of the women were bedridden by the time the company forced them to settle out of court. It was too late for those girls and those like them still working in the factories; their bones will glow for a thousand years. But public opinion was already on the side of the women, and it fueled a turning point in protective legislation, not only in America but in Europe as well.

For a fascinating insight into this topic, here are two links:

The film: Radium Girls (2020) (1:37)

Oh, and by the way: If you find an old, glow-in-the-dark watch face for sale made any time before 1971, give it a WIDE berth.