This week’s adventurous tale is a proverbial rabbit hole; diving into it takes us past the problem of Paris’ 18th century dilemma of dealing with the “explosive” issue of overfilled cemeteries, which forced King Louis XVI to take action: Bury them deeper. Following this problem and its solution into the ground, so to speak, leads us into the massive (1.5 km long) ossuary (bone depository) of Paris. Once you reach the ossuary, which contains the artfully arranged skulls and bones of some six million residents (around three times more than the actual population of central Paris, which as of 2023 was 2.1 million…), you aren’t officially allowed to go any further – because above your head is the bustling city of street cafés, boutiques, and historical buildings. And when someone buys a house up there, they are actually also buying the land on which it stands – which includes their section of the underground maze of mining tunnels and caverns; venturing beyond the official section makes you an intruder on private property or breaking and entering an actual shop – but more on that in a moment. The message above the entrance to the ossuary reads, Arrête! C’est ici l’empire de la Mort. (“Halt! This is the Empire of Death.”). That warning doesn’t stop it from being one of Paris’ most popular tourist attractions.

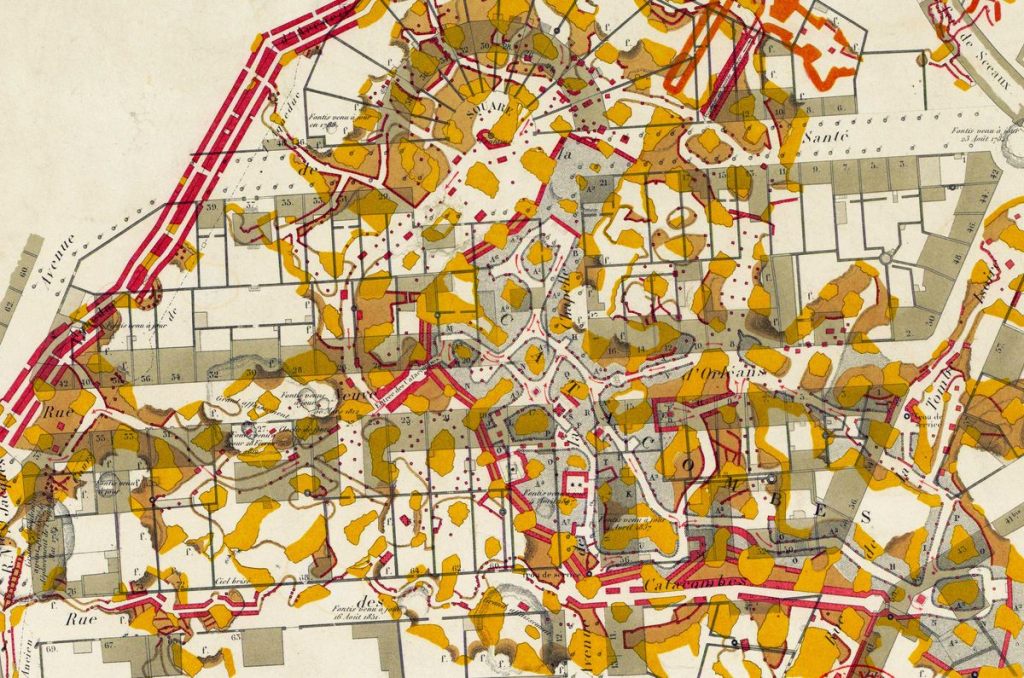

The tunnels, now known as The Catacombs, were originally dug far outside of the small 13th-century city when Lutetian limestone was mined as a local building material (any town or city with a distinctive architecture owes its appearance to whatever was available locally when it was founded – whether wood, stone, thatch or brick). Though no one knows with certainty, as the mining resources were eventually exhausted and the mines abandoned, an estimated 350 kilometres of tunnels undermined the city, which covers some 32 square kilometres beneath Paris… a city beneath a city, as it were.

And yes, buildings have occasionally been swallowed; in 1774, about 30 metres of a street disappeared into a cavern below. This led to the formation of the Générale des Carrières (IGC), an office created in 1777 by King Louis XVI to oversee the mapping and maintenance of the catacombs. During the French Revolution, many things got lost and fell out of collective memory, including the underground map.

Throughout the years, the tunnels have been put to various purposes, aside from the macabre: Mushrooms were cultivated there; beer was brewed, wine aged, and Chartreuse liquors were distilled down there by monks in the 17th century. The city beneath the city had no prime real estate overhead for businesses, and many took advantage of the free space, making access for their customers through the various access points throughout Paris. It also served the French Resistance during world war 2, even though the Nazis also used a section of the tunnels. Now, let’s go back up out of the rabbit hole for a brief moment.

Remember that I wrote officially allowed? Well, a secret maze of tunnels is too much to resist for the adventurous, called cataphiles. But there is a secret society at large down there, too.

When you think of a secret society, you might think of the Luminati or something else sinister; but the Les Ux would be more akin to Robin Hood. The story goes that in 1981, a group of kids were talking after school, and one of them mentioned that he could break into any building in Paris; in fact, his next target was the Pantheon. They didn’t believe him, and so they all went down together – and found out just how easy it was to go wherever they wanted. The Pantheon, which was the tallest structure in Paris until the Eifel Tower was constructed, vacillated between being a church and a secular building several times over its history, depending on the political regime, and it finally became a secular structure in 1885 under the Third Republic. It now is a mausoleum, with famous residents like Marie Curie, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas and Voltaire; but it is also a museum, an art exhibition hall, hosts school events and lectures, and is linked to a section of the catacombs – which is where the group of school friends began their adventures.

During one of their nocturnal outings, the group stumbled upon a narrow passage full of electrical cables; following those, they found themselves in the basement of the Ministry of Communications. No security stopped them and they were able to explore at their leisure. In a drawer, they found the motherlode: A map of the entire catacomb structure. That changed the course of their lives, and they eventually became known as the Les Ux, short for “urban experiment”. These individuals, unknown to anyone but themselves, specialize in safeguarding Paris cultural goods – stepping in when the government can either not afford to or doesn’t care enough to preserve something of cultural or historical value. They seem to think that, unless it’s a big-ticket attraction like the Mona Lisa, things get neglected. For instance, the mission statement of one branch of Les Ux is to reclaim and transform disused city spaces for the creation of zones of expression for free and independent art.

The group, now a full-fledged underground movement, is divided up into teams with seemingly nonsensical names: The Mouse House (an all-female team of infiltrators), La Mexicaine De Perforation (in charge of clandestine artistic events and underground shows), and the Untergunther (specializing in restorations); they also have teams that specialize in things like running internal messaging systems and coded radio networks, a database team, and a team of photographers.

Some of their exploits include restoring a forgotten metro station, a 12th-century crypt, an old French bunker, and a World War 2 air raid shelter. One member, likely from the Mouse House, wrote a detailed report about a particular museum’s security, telling them how many ways she could have broken in and stolen had she been so inclined. She then infiltrated the museum and left the report on the desk of the museum’s head of security. He went straight to the police to press charges. They refused to pursue the matter.

They built an entire cinema complex in the catacombs, complete with a bar and restaurant, where they are thought to have held film festivals for several months or even years before being discovered by the police in a random training exercise. When the police returned to remove the cinema, everything was gone except a note which read, “Don’t try to find us.”

Les Ux has held many events within the Pantheon over the years, including parties and art exhibitions – all vanishing, and leaving the place cleaner when they left, before the museum opened the next day. One night, a team member (from Untergunther) decided to take a closer look at the broken Wagner clock, which hangs over a prominent entrance within the building. Their most public restoration (that we know of so far) was, of course, an embarrassment to the management of the Pantheon: One of the members, Jean-Baptiste Viot, was a professional clockmaker; the team snuck in for nearly a year to restore the clock. They built a secret workshop (complete with armchairs, bookcase, and bar, which they nicknamed the Unter and Gunther Winter Kneipe – German for winter boozer!) high up in the dome of the pantheon, and carried out the clock work by night. Once it was done, they knew that the clock would need to be wound regularly to continue working – so they broke protocol and met with the museum director to tell him the good news. He promptly pressed charges… but there are no laws in France about repairing an expensive clock at their own expense, and the case was dismissed with the comment, “This was stupid!” The museum director hired someone to break the clock, presumably to avoid the hassle of winding it up regularly, and also out of spite for losing his case and his face; the person refused to damage the clock, simply deactivating the mechanism. Les Ux snuck back in to let the clock chime over the days around Christmas, then went back in and removed a component to prevent any further damage the next time spite struck. I’ve read that since that time, the clockmaker of Untergunther has actually been hired by the Pantheon to maintain the clocks.

We only know of a fraction of their activities, of course, because they don’t publicise their accomplishments or events. Below are a few links if you’d like to read more on this fascinating topic! I hope you enjoyed this little exploration as much as I did!

Here are a few links to articles, if you’re interested in learning more:

Meet Paris’ Secret Underground Society (Youtube video)

The Fight Between Cataphiles and Underground Police in the Paris Catacombs

Paris’s new slant on underground movies (with a member interview, explaining how they pulled off the cinema complex)