My husband and I were having lunch recently, and a package of Swedish crackers was on the table; I pointed to the brand name, Pågen. In English, our pronunciation of these vowels would lead us to say pagan /pæg-in/, whereas the Swedish would rather be more like /po-gen/. I just mentioned that English might have sounded similar to that before the Great Vowel Shift, which he’d never heard of (being Swiss, it’s not likely he would be familiar with this aspect of English etymology), so I promised to write a blog about it; here we go!

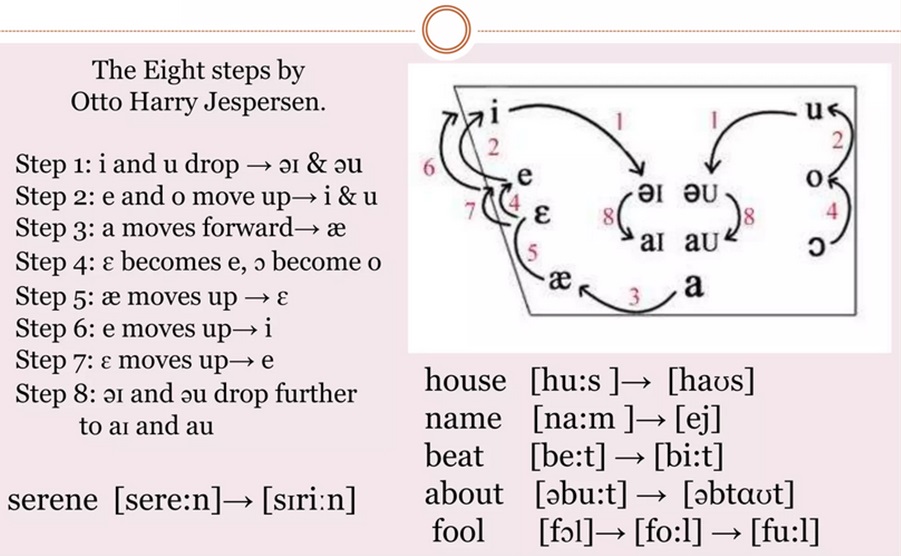

The term Great Vowel Shift was coined by the Danish linguist, Otto Jespersen (1860-1943), who specialised in the English language. Though the GVS is considered a single event (because of the changes being viewed as part of a chain reaction, with each vowel sound changing in a predictable way), the actual transition of English pronunciation was gradual, taking place over about 200 years, from ~1400 to ~1600. The shift began in Middle English, which was spoken from 1066 until the late 15th century – that form familiar to Geoffrey Chaucer (though his pronunciation would be unintelligible to us, his words still survive through his famous Canterbury Tales) – into Early Modern English (from the beginning of the Tudor period through to the Stuart Restoration period); Shakespeare would have been familiar with it. From there, English transitioned into Modern English in the mid-to-late 17th Century.

The main changes were that, from Middle to Early Modern English, the long vowels shortened; weef became wife, moos* became mice, beet became bite, and so on. (*The word moose entered English through Native American languages in 1610). I will also mention that in Scottish, a lot of the older vowel pronunciations still exist; house is still huus, full is homophonous with fool, etc.

Here’s a look at just how the English vowels shifted:

If you’ve been paying any sort of attention to English, you’ll know that our spelling is a bit chaotic; the language is full of homonyms, which are divided into either homophones (words that sound the same but have different spellings, e.g. beet and beat; bear and bare; to, too and two), or homographs (two words with differing meanings, same spellings, but not necessarily the same pronunciation: e.g. bank [of river; finance] or agape [with mouth open; love], or entrance [a way inside; to delight]) or tear [ripping; crying]. These -graphs and -phones came into English from regional dialects that were transported as migration and cultural mixing took place, and the GVS added its two pennies to the mix. Just think of the variety we have in the sounds /ea/ (bread, beat, bear, break); /oo/ (look, spool, blood); or /gh/ (through, cough, sight).

Certain factors contributed to the speed of language shift: The Black Death (1346-1353) wiped out up to 50% of Europe’s population. Stop a minute and let that sink in. What if the population of your town were reduced by half? And the next town, and the next. That single event changed the course of history on many levels; surfs could finally demand better wages wherever they ended up settling; if you lived in a town that no longer had the skills of a baker, blacksmith, or any other trade you’d depended on, you’d move to where those services existed – and jobs existed – and that meant places that had been hit the hardest by the plague and thus where everyone else was migrating, such as London. As mass movement followed the epidemic, people brought their dialects and their spellings with them. It began to converge into a new, distinct way of speaking, thinking and spelling. The geopolitical climate of the time also influenced English; England and France have been annoying each other for over a thousand years; whenever England was enamoured by all things French, they tried to emulate their pronunciations. That influence came and went; in one such moment, the pilgrims set sail for America (1620), taking a time capsule of the language with them, while England’s English continued to be influenced by French up until the French Revolution, when it quickly fell out of favour in England, though the changes had already taken place (one example is the American /k/ in schedule, closer to the original Latin, while the English say /sch/ without the /k/, which is closer to the French cedule). This factor of influence also affected differences of speech between the lower class and upper class at that time; the upper class wanted to sound more posh, more fashionable, and above all, not like the lower class.

A major contributing factor to our chaotic spelling is that ca. 1440, the Gutenberg printing technique was introduced, and by the 1470s, William Caxton had imported the invention to England; we have him to thank for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales being known today, as that was the first book he printed in England. We also have him to thank for the influence of Chancery English (the English used by the secretariat of King Henry VI) in the standardization of the language, as he used it as his own guidelines in printing. The vowels had already begun to shift by that time; enter the written word, a rise in literacy, and you have the jumbled effects of “mid-shift” on English spelling – people began to adapt their pronunciation to the written word, so whichever form the printer used is the one that began to prevail, even though some sounds were still in transition. Like nailing down jelly. You could say that many of our odd spellings are simply a snapshot in time.

It is also important to point out that the GVS didn’t have the same influence everywhere: The main changes occurred around London, but the farther away you move from that epicentre, the less the effects on the local dialects, which still holds true today – though gradual merging has allowed people from, say, Cornwall, to understand people from Yorkshire – which wouldn’t have been the case centuries ago. Even though they can understand each other, their dialects are still distinct. I’ve already mentioned that Scots English (as opposed to Gaelic) still retains many of the longer vowels long since lost in standardized English; being so far from London, they simply ignored them. English may be taught in their schools, but Scots dialects prevail in the home and hearth. Regional dialects in English exist the world over, and though spelling and pronunciation may differ from region to region, and the language continues to be a living, breathing, growing and changing being, it’s still a language that enables the modern world to communicate, whether English is their mother tongue or not.