Today is both a palindrome and an ambigram! At least, in countries where the date is written day, month, year…

You can read it front to back, back to front, or upside down. Now ya know.

Today is both a palindrome and an ambigram! At least, in countries where the date is written day, month, year…

You can read it front to back, back to front, or upside down. Now ya know.

I have hundreds of recipes pinned to dozens of Pinterest boards, so I come across a wide range of offerings. Nowadays, the images have to be perfectly lit and photoshopped to make them look appealing; it’s like sugar in pre-packaged foods… we’ve gotten so used to the artificial visual flavour that if a photo were undoctored in some way, it would be glaringly out of place. But what is often missing is the same attention to detail in the writing. I’ve seen “tablespoon” misspelt a few ways, or the abbreviations as Tbs., tb, tbs, tbsp, T., etc. So which one is correct? And do the forms or the etiquette of choices differ between print and online versions?

I pulled out a cross-section of cookbooks in my library and thumbed through them; I took older, newer, American and British, and I scoured online recipe sites like Betty Crocker; here’s what I discovered:

As with any kind of writing, some things are a matter of personal preference; at that point, where there is no one grammar rule to apply, the most important thing is to be consistent throughout the manuscript.

If you’re thinking of writing a cookbook (or any other manuscript for that matter!), I would recommend keeping what is called a style sheet; this is used in publishing houses where several people will have the manuscript in hand at some point; this sheet prevents someone else from undoing choices – they can look at the style sheet and know that it was an intentional decision, and leave it; otherwise the risk is that one man’s capital is another man’s lower case, and so on.

As an author, the style sheet is my running list of decisions to keep me on track as I write; it can include sections for punctuation (have I decided to go with British or American English punctuation for things like Mr / Mr.?), unusual capitalisations (for me, one issue was when to capitalise “sir” as a substitute for a proper name – I could always refer to my sheet when in doubt), abbrevitation/contraction choices, etc. It could also include a record of my choice of fonts, spacing between sections, indentations, and so on. I have a section for my “cast of characters” – to remember how I’ve spelled a name, or what I’ve named an infrequent cast member. I might include an abbreviated description of a character so that I don’t give them green eyes in chapter one, and blue eyes in chapter ten. What you can include in your style sheet is endless… foreign terms/spellings, reminders to check validity of hyperlinks, punctuations such as en- and em-dashes, how you’ve written specific gadgets (capitalised or not, hyphened or not, etc.). Below is a basic style sheet template to get you started.

No matter what you’re working on, hone your craft, and keep writing!

Filed under Articles, Grammar, Nuts & Bolts

Spell checker in action

I’ve been editing, tweaking, editing, and tweaking this week; not to mention editing. Over the years I’ve used a wide variety of tools, such as Scrivener, but have found that, for me, the best combination is MS Word and my brain.

One of the tools I’ve also been using recently is a new one for me: The Grammarly app in Word. I’m of a mixed opinion about it. Do any of you use this app with your manuscript? If so, what is your experience/impression?

So far, the app is batting less than 1 out of 10; in other words, of 10 “critical errors” that it points out, only 1 of them is legitimate. I’d say the average is more like 1 out of 15 or 18. There is also a version of this app, which requires a monthly or yearly subscription, that will expand its range of editing suggestions; but before I go that route I want to know that the app actually works in the free version. So far, it’s more static than editing aid.

Now to be fair, my manuscript is not the average; it’s got words like en queue (the hairstyle of men in the 18th century), and odd terminology to do with nautical actions or environments. But some of the errors that it points out, such as those to do with commas, are actually correct (e.g. pointing out the second comma of a parenthetical phrase as out of place). Most of the time the suggestions that it makes are just downright wrong in the context; it proves that language is a fluid concept, and nearly impossible to intelligently simulate in a computer program. It also means that we are far better off becoming fluent in grammar rather than relying on ANY program to correct our writing!

Having said that, I still appreciate it because it forces me to think through a decision, whether that be sentence structure, punctuation, or phrasing. Sometimes it sends me in search of confirmation for a grammatical assumption I’ve made; rarely am I surprised by what I find, but it nevertheless helps to solidify the right way of writing something in my mind. For the most part, I have the app turned off (a great function – the only reason I still use it!), just running it through sections at a time as my other editing nears an end.

Are there any programs or apps that you use for editing? If so, what is your experience? Please share in the comments below!

Filed under Articles, Musings, Nuts & Bolts

Let’s face it: When writing dialogues between characters, repetition can tend to sneak up on us: He said, she said, he whispered, she whispered, and so on. There are a few tricks I’d like to share with you that I’ve learned along the way; one is regarding grammar, and the other is my own twist on dealing with the issue.

Regarding grammar, action verbs can often take the place of the more passive verbs (such as said): “He said, ‘I’d like that.’” can be spiced up by giving him an action to do (“He picked up the travel brochure and flipped through it: ‘I’d like that.’”) The second sentence gives more context, and is more visually engaging for the reader. Keep in mind that every word should count; don’t pad out the sentence just for word count, or make each exchange in the conversation a prop advertisement; but punctuating a dialogue with such moments can bring it to life.

My own twist is a literal one – a CD: I took an old one, covered both sides with blank CD labels, and wrote all of the synonyms (listed below) for say and said in a spiral, starting in the centre, changing colours for each new letter of the alphabet. To use it, I just put it on my finger and spin it around as I read through the spiral until I find the word that best fits my sentence. I have several such CDs within reach of my computer (another CD, for instance, is for walk synonyms, and another for lie/lay); if you make enough of them, you could keep them in a CD pouch. Here’s my list of the words around Say (click on the image to enlarge):

A word of advice to those of you for whom English is not mother-tongue: Depending on the word, the sentence structure may need to be adapted. If you’re unsure how to use a word, I would recommend looking it up on Wordnik, and reading the examples on the right-hand side of the page; then choose the sentence structure, prepositions, etc. that are more frequent than not.

I hope that this list helps you say what you want with the variety and precision you’re aiming for! Feel free to reblog! Feel free to print this list out and use it; if you pass it on online please put a hyperlink back to this blog, or recommend my blog if you pass it on by word of mouth… thank you!

If you can think of any words or phrases to replace say or said that I missed in the list above, please put them in the comments below! Keep writing!

Filed under Articles, Lists, Nuts & Bolts, Research, Writing Exercise

This past week I’ve been quite busy getting ready for a big change in our lives: Taking in an exchange (high school) student for nearly a year. She’s coming from Thailand, and wants to learn German; I’m not sure she knows what she’s getting herself into, as we don’t speak the German she will need to learn for school; we speak Swiss German, which is about as similar to High German as Old English is to modern English.

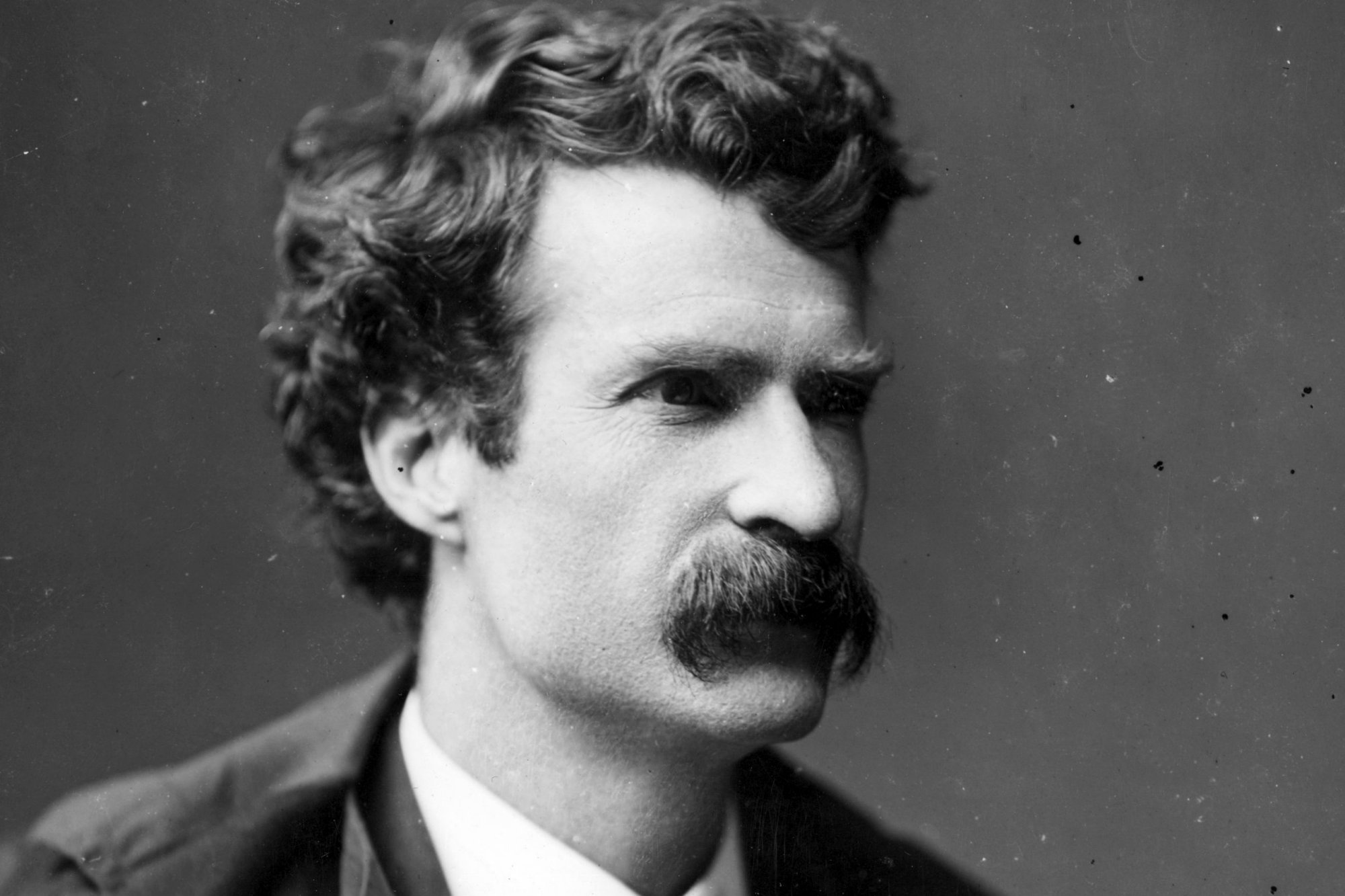

In preparation, I’ve been doing a bit of spring cleaning too – might as well, right? My main work room, our library, is also where I keep folders full of stories I’ve saved over the years, and while sifting through them I was reminded of an article about Mark Twain’s observations on the German language. I found what I was looking for in a Kindle book; it would be astonishing (and perhaps a bit discouraging) to Mark Twain if he could see his entire life’s work reduced to an e-book for less than $ 2.00, but so it is. I was surprised to find a short description of his time in Switzerland, as part of his Grand Tour no doubt. And as I mentioned above, the German dialects we speak are not the German Mark Twain describes, so I can laugh along with the rest of you (and I can laugh at the fact that the WordPress spell check is going berserk). I’ll need to resort to High German for the sake of our exchange student, but it grates on my ears and tongue like sandpaper on the eyeballs. Mark Twain seems to have had similar sentiments. I will first share his impression of Switzerland, and then bombard you with his opinion of the German language. This post is a bit longer than my usual offering, but Twain is well worth it! So put your feet up, get a cuppa, and enjoy!

Interlaken, Switzerland, 1891.

“It is a good many years since I was in Switzerland last. … there are only two best ways to travel through Switzerland. The first best is afloat. The second best is by open two-horse carriage. One can come from Lucerne to Interlaken over the Brunig by ladder railroad in an hour or so now, but you can glide smoothly in a carriage in ten, and have two hours for luncheon at noon—for luncheon, not for rest. There is no fatigue connected with the trip. One arrives fresh in spirit and in person in the evening—no fret in his heart, no grime on his face, no grit in his hair, not a cinder in his eye. This is the right condition of mind and body, the right and due preparation for the solemn event which closed the day—stepping with metaphorically uncovered head into the presence of the most impressive mountain mass that the globe can show—the Jungfrau. The stranger’s first feeling, when suddenly confronted by that towering and awful apparition wrapped in its shroud of snow, is breath-taking astonishment. It is as if heaven’s gates had swung open and exposed the throne. It is peaceful here and pleasant at Interlaken. Nothing going on—at least nothing but brilliant life-giving sunshine. There are floods and floods of that. One may properly speak of it as “going on,” for it is full of the suggestion of activity; the light pours down with energy, with visible enthusiasm. This is a good atmosphere to be in, morally as well as physically.

“After trying the political atmosphere of the neighboring monarchies, it is healing and refreshing to breathe air that has known no taint of slavery for six hundred years, and to come among a people whose political history is great and fine, and worthy to be taught in all schools and studied by all races and peoples. For the struggle here throughout the centuries has not been in the interest of any private family, or any church, but in the interest of the whole body of the nation, and for shelter and protection of all forms of belief. This fact is colossal. If one would realize how colossal it is, and of what dignity and majesty, let him contrast it with the purposes and objects of the Crusades, the siege of York, the War of the Roses, and other historic comedies of that sort and size. Last week I was beating around the Lake of Four Cantons [Vierwaldstättersee], and I saw Rutli and Altorf. Rutli is a remote little patch of meadow, but I do not know how any piece of ground could be holier or better worth crossing oceans and continents to see, since it was there that the great trinity of Switzerland joined hands six centuries ago and swore the oath which set their enslaved and insulted country forever free…”

What he had to say about the German and their language is quite different, however:

“Even German is preferable to death.”

“Surely there is not another language that is so slipshod and systemless, and so slippery and elusive to the grasp. One is washed about in it, hither and thither, in the most helpless way; and when at last he thinks he has captured a rule which offers firm ground to take a rest on amid the general rage and turmoil of the ten parts of speech, he turns over the page and reads, “Let the pupil make careful note of the following EXCEPTIONS.” He runs his eye down and finds that there are more exceptions to the rule than instances of it. So overboard he goes again, to hunt for another Ararat and find another quicksand.”

“German books are easy enough to read when you hold them before the looking-glass or stand on your head—so as to reverse the construction—but I think that to learn to read and understand a German newspaper is a thing which must always remain an impossibility to a foreigner.”

“…in a German newspaper they put their verb away over on the next page; and I have heard that sometimes after stringing along the exciting preliminaries and parentheses for a column or two, they get in a hurry and have to go to press without getting to the verb at all. Of course, then, the reader is left in a very exhausted and ignorant state.”… “It reminds a person of those dentists who secure your instant and breathless interest in a tooth by taking a grip on it with the forceps, and then stand there and drawl through a tedious anecdote before they give the dreaded jerk.”

“Some German words are so long that they have a perspective. Observe these examples:

“Some German words are so long that they have a perspective. Observe these examples:

Freundschaftsbeziehungen.

Dilettantenaufdringlichkeiten.

Stadtverordnetenversammlungen.

These things are not words, they are alphabetical processions. And they are not rare; one can open a German newspaper at any time and see them marching majestically across the page—and if he has any imagination he can see the banners and hear the music, too. They impart a martial thrill to the meekest subject. I take a great interest in these curiosities. Whenever I come across a good one, I stuff it and put it in my museum. In this way I have made quite a valuable collection. When I get duplicates, I exchange with other collectors, and thus increase the variety of my stock. Here are some specimens which I lately bought at an auction sale of the effects of a bankrupt bric-a-brac hunter:

Generalstaatsverordnetenversammlungen.

Alterthumswissenschaften.

Kinderbewahrungsanstalten.

Unabhängigkeitserklärungen.

Wiedererstellungbestrebungen.

Waffenstillstandsunterhandlungen.

Of course when one of these grand mountain ranges goes stretching across the printed page, it adorns and ennobles that literary landscape—but at the same time it is a great distress to the new student, for it blocks up his way; he cannot crawl under it, or climb over it, or tunnel through it. So he resorts to the dictionary for help, but there is no help there. The dictionary must draw the line somewhere—so it leaves this sort of words out. And it is right, because these long things are hardly legitimate words, but are rather combinations of words, and the inventor of them ought to have been killed.”

“My philological studies have satisfied me that a gifted person ought to learn English (barring spelling and pronouncing) in thirty hours, French in thirty days, and German in thirty years. It seems manifest, then, that the latter tongue ought to be trimmed down and repaired. If it is to remain as it is, it ought to be gently and reverently set aside among the dead languages, for only the dead have time to learn it.”

Quotes from the Complete Works of Mark Twain (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.