Jumièges Abbey is one of the oldest Benedictine monasteries in Normandy; to dive into its history is akin to diving down Alice’s rabbit hole. For instance, I could say that the abbey was sponsored by the Frankish Queen Balthild, as she persuaded her husband, King Clovis II, to donate land to the Frankish nobleman Filibertus in order to found an abbey. But to know who she was, ah, that is where the intrigue begins.

Who and where were the Franks, when were they a thing, and what are they to us today?

Who, where and when: They were a Western European people who began as a Germanic people along the lower Rhine (which flows from Bonn, Germany, and ends up in the North Sea at the southwestern corner of the Netherlands), along the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, they expanded their scope of rule as the Western Roman Empire began to collapse, and they imposed their power over many post-Roman kingdoms and beyond. That’s the crux of the matter though, as with any political history, it’s far more complex than that. The Franks are distinguished into two main groups by historians: The Salian Franks, to the west, and the Rhineland Franks, to the east.

In the mid-5th century, The Salian king, Childeric I, was a commander of Roman forces against the Gauls, most of whom Childeric and his son, Clovis I, conquered in the 6th century. Clovis was the first king of the Franks to unite the Frankish tribes under one ruler, and he founded the Merovingian dynasty – which ruled the Frankish tribes for 2 centuries. Clovis, in essence, is known as the first king of what would become France. As a side note, the Frankish name of Clovis is at the root of the French name of Louis, borne by eighteen kings of France.

Now, back to Queen Balthild (AD 626 – 680): Sold into slavery as a young girl, she was beautiful and intelligent. She served in the household of Erchinoald, the mayor of the palace of Neustria to Clovis II. Her master, a widower, wanted to marry her, but she hid herself from his sight until he married someone else (apparently the household of servants was numerous enough to enable her to avoid her unwanted suitor). Perhaps through Erchinoald’s notice of her, she came to the attention of Clovis II, who proposed to her and was accepted; hiding herself away may have been a political tactic to gain a higher rank with the king than with the mayor; According to the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi by Stephen of Ripon (written around AD 710), Bathild was a ruthless ruler, in conflict with the bishops and perhaps responsible for several assassinations. Some historians interpret Queen Balthild’s association with founding monasteries as a way of balancing or neutralizing aristocratic opposition to her rule. By installing her own bishops and donating lands for abbeys, she strengthened her own power as ruler (she was regent during the minority of her son). To put that in proper perspective, she was no different than most male counterparts of her day. [I could go off on a tangent about how adjectives differ when applied to the male or female state of affairs (a man is ambitious; a woman is pushy or ruthless), but I won’t. Yet.] From most accounts, however, she was pious and humble. Whichever way you butter that croissant, in ca. 860 she was canonized, thereafter to be referred to as Saint Balthild…

In 654, Balthild gave a parcel of royal land to Philibert, or Filibertus, on which he founded the Notre Dame de Jumièges. His main spiritual influence was that of the Irish monk, Columbanus (who founded several monasteries in the Frankish and Lombardi kingdoms). The abbey flourished until the Viking invasions of 841 (Remember Rolf Ganger?), which caused disruptions to its first momentum, but it soon began to prosper again. The church itself was rebuilt between 1040 and 1066; it was dedicated on 1 July 1067, with none other present than William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy and King of England (1066 and all that). The patronage of such a nobleman ensured the abbey’s success.

Jumièges Abbey was, like any abbey of its time, a veritable town. The church was only the heart of the community; there was a 14-acre enclosed park, terraced gardens, the abbatial manor, a bakery, landscaping to evoke biblical scenes, a hostelry, the 14th century “Charles VII” walkway (a covered walkway between the Notre Dame and St Peter’s church, named after the fact that Charles VII and his favourite mistress visited the monastery), and the cloister.

The next major disruption was from 1415, when the monks were forced to regularly seek refuge in Rouen as the English occupied Normandy during the Hundred Years’ War. The abbey eventually recovered and began to flourish again, until the whole province was plunged into the chaos of the Wars of Religion (1562-1598), resulting in the population’s decimation and famine. In 1649, the abbey was taken over by a Benedictine congregation, when some of its former glory was revitalized. Having survived all of that, its ruin came at the hands of the French Revolution, when it was sold as a “national property” and turned into a stone quarry (seen only as a source of ready-cut stones). At last, its historical value was recognized in the 19th century, putting an end to its wanton deconstruction.

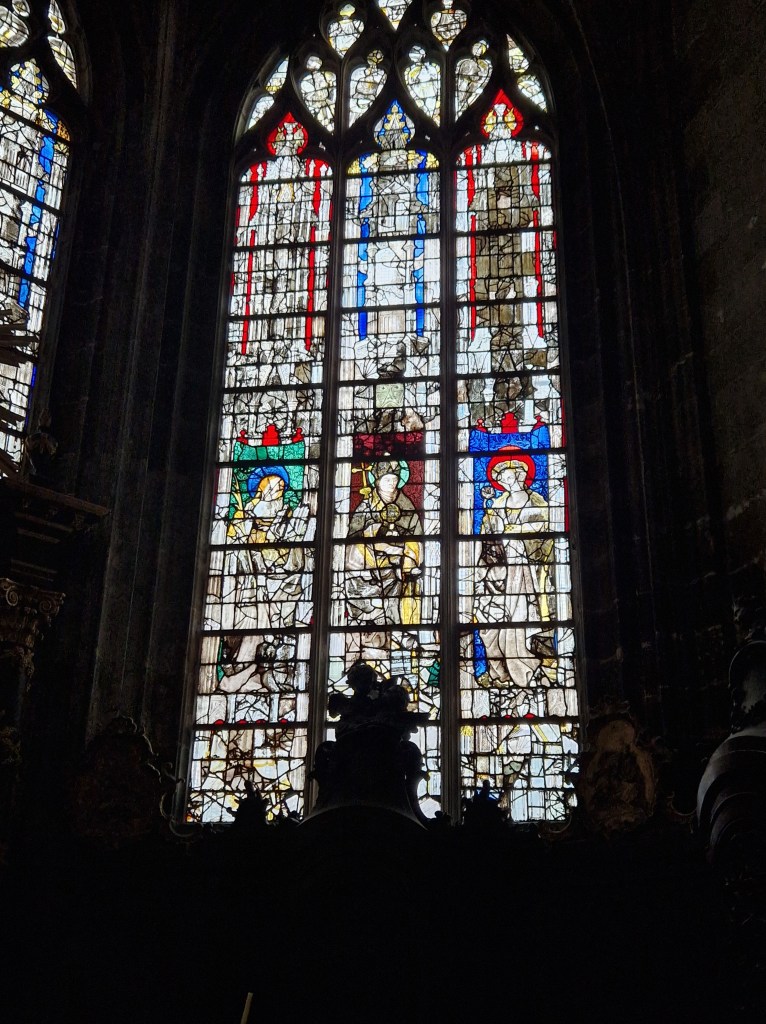

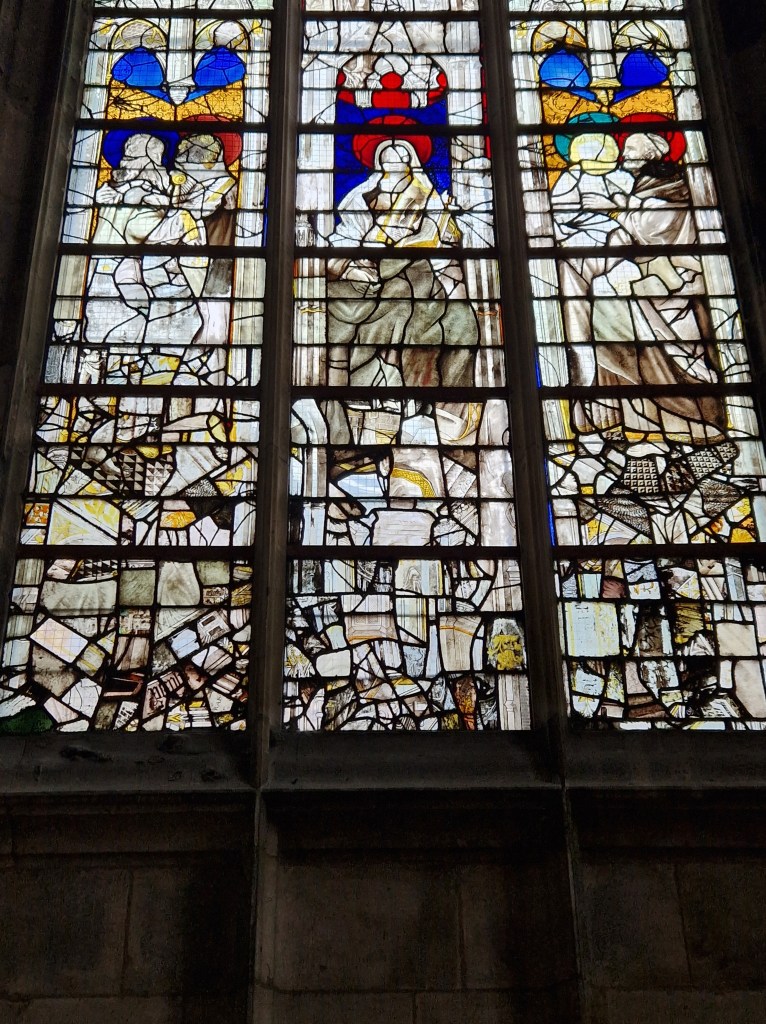

When we visited the abbey last summer, its grandeur, although only ruins today, is still evident; when it was at its height of prosperity, it must have been an awesome sight to behold! In the photos below, which I took during our visit, you can see evidence of the various phases of destruction and reconstruction. Enjoy!