My quirky brain went down a rabbit hole last week; as I was putting away groceries into glass jars (for that explanation, please click here), I wondered who had been the genius behind the thread around canning jar lids, or, as most of my jars use, the bail closure.

Just to clarify terminology: Here is a threaded jar, a type of screw-on lid that is either one part or two:

Here is a jar with a bail closure, aka flip-tops, lightning jars, known also by their various brand names, e.g. Fido, Le Parfait, Kilner:

A third type of jar, German-made, is the Weck jar, with metal clips and a glass lid. I don’t like using these, so you won’t find them in our house.

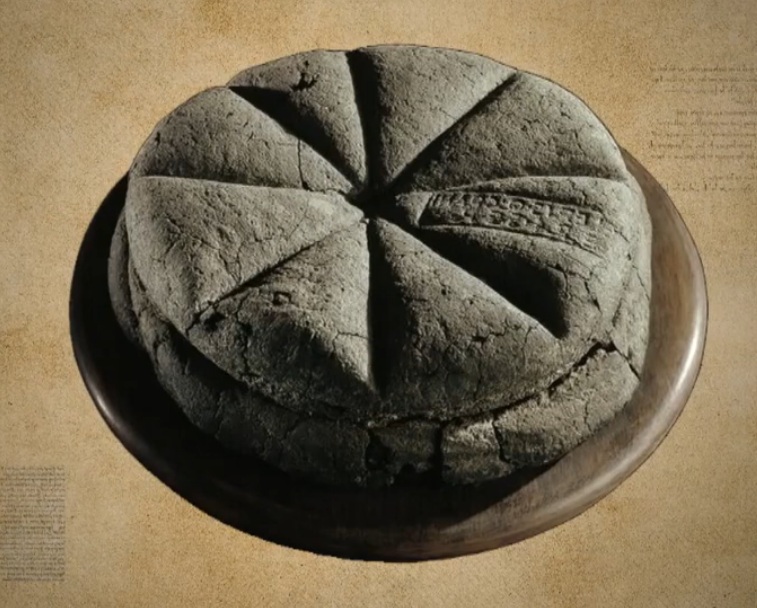

Closures have been an issue for thousands of years; ancient amphoras, which were used to transport wines and oils, were sealed with wood, cork, or a ceramic or pottery lid sealed with a type of mortar. Archaeology has many examples of clay or pottery pots with lids, Norse ornate metal containers with lids, and even ancient Egypt’s canopic jars, with their ornate lids. Another variety of closure is found on wooden barrels, which have side holes called bungholes, plugged with a cork or other wood.

The threaded jar lid was invented by the tinsmith John Landis Mason in 1858. Prior to his invention, a glass lid was laid atop an un-threaded canning jar and sealed with hot wax. It was messy, and if it wasn’t done right every time, it could allow dangerous bacteria into foods. Before refrigeration, the only way to preserve garden produce was basically to can with a wax seal and take your life into your hands. There were other preservation methods, such as drying, salting, smoking or pickling, but the new way of preserving offered a convenient, faster alternative; Mason’s threaded lids, combined with a rubber ring and a threaded glass jar, revolutionised canning. Unfortunately, he was not a savvy businessman, and though he filed a patent for the threaded screw-top jars, he failed to patent the rest of the invention, such as the rubber gaskets. He let the patent expire in 1879, and manufacturers took the idea and ran with it. Mason never made a fortune; in fact, he died in poverty in 1902. But his name lives on in the common term, “Mason Jars”. The concept is now used with countless products, from drinks to shampoos to household cleaners.

The invention of the bail closure design is a bit murkier: In the early 1840s, the Yorkshireman John Kilner invented the Kilner jar, using the rubber seal and wire bail closure.

In 1893, beverage bottles began using the Hutter stopper – a porcelain plug with a rubber gasket held in place with a metal strap.

In the 1930s, the La Parfait jars began production in Reims, France, by Verreries Mécaniques Champenoises, a historic French glassmaker.

The Bormioli family is an Italian name associated with glass-blowing since the Middle Ages; among their many brands is the Fido airtight jar, using the bail closure, which began production in 1968.

I personally have Kilner, La Parfait and Fido bail-closure jars, as well as many screw-top jars similar to Mason from these companies.

Do you use any such jars for storage in your home? Do you use them for canning or storing dried goods, or both? Please comment below!