From cave paintings to stone tablets to modern paper forms, people have been expressing themselves and capturing moments in time for millennia, driven by an innate desire to record their lives. My personal belief is that our creativity is an expression of our Creator’s own character, whether we know Him personally or not; it’s what drives us to share our lives with others, to relate our experiences and preserve them for posterity.

With the dawn of the internet, interconnectivity has become something we often take for granted, but it is amazing nevertheless. No other generation before us has literally had the world at its fingertips. We can not only learn about a country on the other side of the planet, but we can also learn something from someone on the other side, too. Seeing things from others’ perspectives and allowing their ways of seeing the world to teach us new skills is a privilege.

In modern times, journalling has never been easier and has never had as many possibilities; they come in all shapes, sizes and varieties:

The first that comes to mind is the daily journal: That may be something as simple as recording what you did in the day or making a note if you bought something like a new laptop or a household electronic gadget; it may also be a place to record deeper ideas, or to form thoughts that help us work through an issue we’re facing. I’ve been keeping a daily journal since I was around 8 years old, and with few exceptions, I still have all of those journals on our library shelves! One, from my time in Hawaii, was lost somewhere along the way, and another was in a suitcase stolen back in 1992 when I was living in Scotland. We may not think that recording such mundane, daily things has any significance, but in a hundred years, scholars will be clambering to find out how much things cost back then, or what common people did daily. There are many museums which collect journals for that very reason.

Sometimes people need a boost of focus with what’s known as a productivity journal: This might be used to record specific goals and timelines, or measurable progress toward a project or health goal such as weight loss (this could be called a food journal if your sole focus is dietary). It can be used to track steps toward a goal, a hobby or a target. Closely related to this journal is what’s known as a bullet journal: This includes things like to-do lists, checklists and trackers. I use this method when I’m in the proof-reading phase of a book; the more experience I have in writing, the shorter those checklists and watch-out-for lists get, but it’s still a useful method for staying focused. Related to these is a planner journal, also known as an agenda, used to plan appointments and events and to remember activities and birthdays. Some people like these as physical paper, while others have phone or computer apps with the same functions.

A gratitude/happiness journal is another type of motivating diary. In it, you record things you’re grateful for; you practice mindfulness and focus on the positive. In this batship crazy world we live in, such a journal is almost a necessity!

A reading journal is a way of tracking what you’ve read, impressions or side notes while reading, and a to-be-read list.

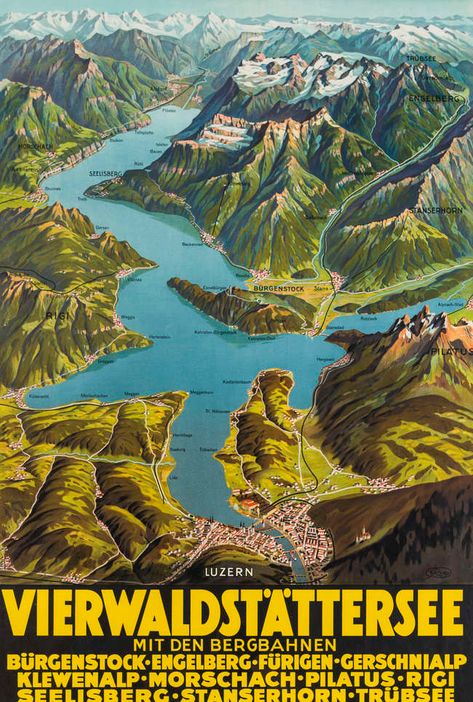

Travel journals are another popular form of recording holiday memories. Whenever we have travel holidays, e.g. renting a motorhome, I take along a homemade notebook. I keep track of mileage, expenses, and where we stop or visit along the way. I will also put things like postcards, ferry tickets, or tourist brochures in the notebook. We have a growing collection from holidays in Scotland, Norway, New Zealand, and across Switzerland.

The journals above are primarily text-centric; but another variety focuses on the aesthetic and visual, a way of expressing creativity while practising mindfulness through colours and textures.

One visual form is a nature journal; among the most famous of this kind is The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady (1906), by Edith Holden. It’s still in print, and her drawings, as well as her handwriting, are exquisite!

Another visual form is commonly known as a junk journal; I would say it is the modern iteration of scrapbooking, though there are differences: Scrapbooking is focused on preserving memories of certain events or phases of life through photos and/or memorabilia like theatre tickets. Junk journalling began as a freeform way of journalling using (as the name implies) junk – packaging, recycled materials or papers, and things that might usually be thrown away otherwise. Nowadays, many junk journalists use craft papers, digital graphic kits, and many make their own digital visuals and use their social media to promote and sell their products by showing how to use them in “junk” journals. The camps are divided on the issue – can it still be called a “junk journal” when it’s mainly comprised of printed materials specifically for that purpose? I personally don’t junk journal, per se – I appreciate many of the techniques developed to fill such a journal, but I tend to be more of a practical crafter – if it can be aesthetically pleasing and practical, I’m all in; but I have neither time nor space to fill a journal with random tags and stuffers just to make it thick and interesting. One journal I have made is a book of writing prompts; it’s of practical use, with interesting pages drawn from junk journalling techniques. Nothing is in the book just for show; everything is there to inspire toward creative writing.

Other types of visual journals are art journals: These can take the form of painted pages, mixed media, or hand-drawn artwork. I have three types of art journals: One is a book I take with me on holidays, in which I mainly draw calligrams – impressions, nature, street art, or museum exhibits drawn from words. I usually do a sketch first, then research the topic, then fill in a condensed version of that research to fit the drawing, replacing the shape and contours with words. Another art journal I maintain is a mixed media journal; I add to this one as inspiration and time collide. The third art journal is what I call my inspiration book: When I come across an idea that I want to remember, such as a way to make a journalling pocket or insert, I will make a sample and put it in this book. I have things in the book that I have sold in our annual Advent market – samples of popular items with measurements and details to remember.

Another type of art journal, perhaps closely related to the food journal above, is a recipe journal: It’s an artistic expression with the purpose of creating an heirloom book of favourite or family recipes. They might be made as a bridal gift, birthday gift, or retirement gift.

There are a dozen other ways to journal: Bible journalling, therapeutic, morning brain dumps, dream journalling, mood tracking, and the list goes on.

Question:

Do you journal? If so, which form does it take? Do you use several journal expressions, and if so, are they used in combination or separately?