Throughout history, people have always been fascinated by thinking beyond their own known world; before widespread writing and reading, ancient cultures thought about their own mortality (which, in some ages, wasn’t that far off) and the afterlife. Various cultures prepared for the afterlife in their own ways: The Egyptians removed organs and embalmed the rest, making sure to send on the heart & co. in separate jars (except the brain – who’d need that in the next world?), then sent them on their way with an army of servants (killed for the occasion); the Vikings buried their most honoured dead within a ship with their favourite animals and servants (ditto). Other cultures built pyres to send their loved ones up in smoke.

When writing came along, at first it was used to capture the past and the natural world, ala Pliny the Elder; poems, sagas, verbal tales and folklore began to be recorded; we have such writings still with us today: The Greek Epic Cycle, the Orkneyinga Sagas, the Heimskringla, the Poetic Edda.

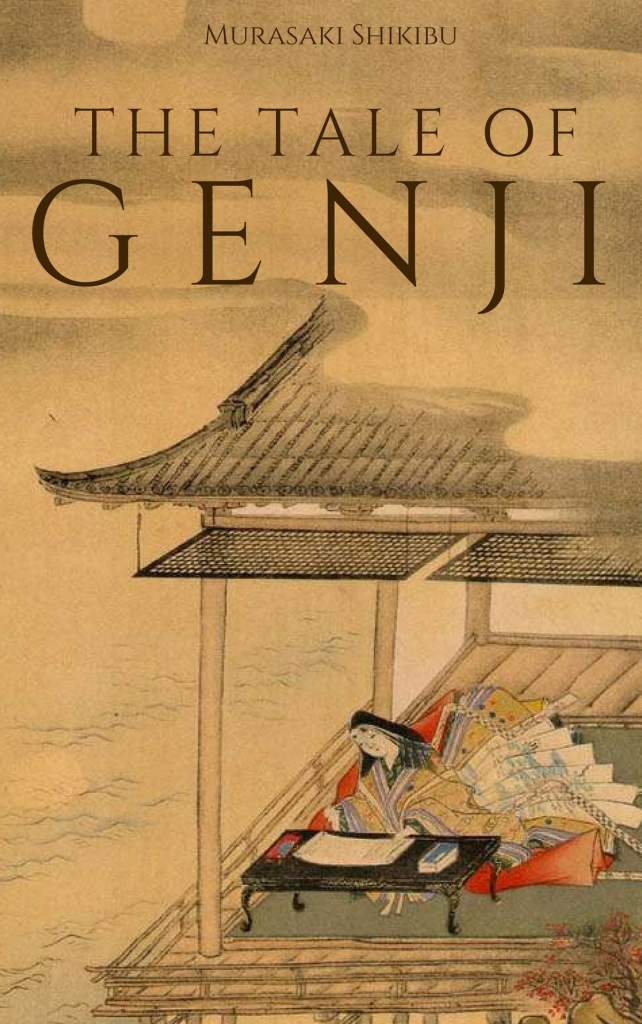

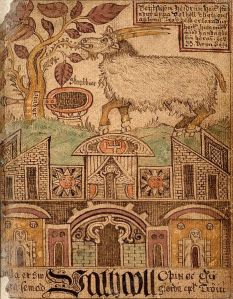

The first novel came along only 1,000 years ago: The Japanese epic The Tale of Genji was written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu; novels were, for several centuries more, considered on the bottom rung of the literary hierarchy ladder, far behind “serious works” like history. Ironically, Mark Twain referred to history as “fluid prejudice”; it was nearly always recorded by powerful (white) men – hardly ever by a commoner, a member of an ethnic minority, or a woman. The interpretation of events was firmly in the hands of the conquerors. Because of that fact, for instance, we know more about Rome’s version of ancient Britons (Picts, Celts) than we do from their own artefacts; most Celtic and Pictish art is found outside of the UK – many carried off by the Vikings, but that’s another tale. Hollywood has helped perpetuate some of those ancient Roman notions (think of a blue-faced Mel Gibson in Braveheart).

In fact, we don’t even know what the Picts called themselves – the term derives from the Latin Picti, first seen in the writings of Eumenius in AD 297. It can be interpreted (dangerous words) as “to paint” – but there is no evidence that any people groups in northern Britannia painted themselves. Picts is simply a generic term for any people living north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus who fought the Roman Empire’s advancements into their territories. Again, the ink of history flowed from a Roman stylus.

Even Jane Austen herself didn’t begin publishing her novels under her own name. She was a single young woman – for shame that she would dare stain the male-hallowed ground of literature. The saga of how she got published speaks to her tenacity and the support of her family. But she got the last laugh, becoming famous within her (short) lifetime, and she is far better known today than any of the stuffy old men who wrote “proper” books of her day.

The insatiable fascination with other perspectives than our own explains why novels are so popular today. They take us into another time, place and situation, leading us through a story that, if written well, we can relate to and perhaps learn something from. In 1726, Jonathan Swift gave us Gulliver’s Travels. Though he originally wrote it as political satire, to “vex the world rather than divert it”, we know it still today. The fascination with someone being a giant in one land and a miniature in the next grabs our imagination; he travels to floating kingdoms, to an island of immortals, a la Death Becomes Her, and a land of talking horses.

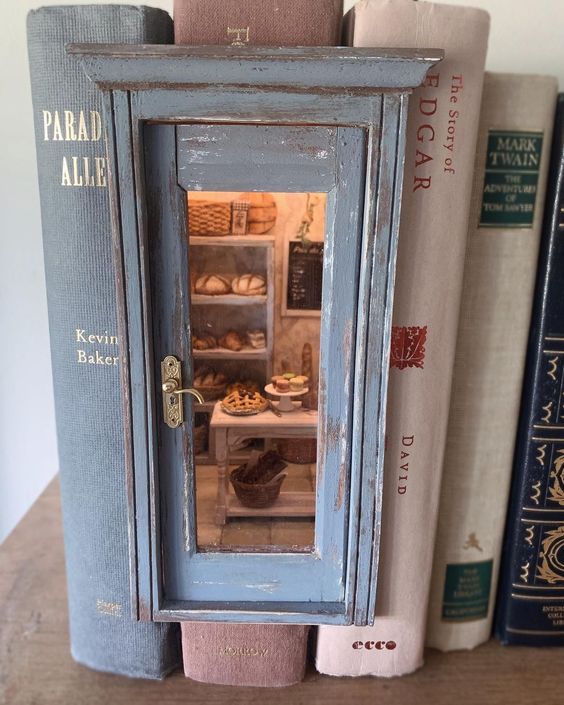

In the age of internet, visual arts have expanded as far as the global imagination can span: Not only paintings or drawings, but even crafts take us into another perspective. I recently saw a series of images in which people have taken the humble walnut shell and turned them into tiny worlds with bookshelves, ladders, lamps, beds and creatures. Book nooks are popular, too: A tiny village, street, or room within the space of a book on a shelf. Science fiction art takes us off-planet.

Films are visual perspectives that take us into other worlds, times and places: When George Lucas showed us a “commonplace” bar scene on Tatooine in the Mos Eisley Cantina in Star Wars, he blew our minds and kicked off a new era of visual storytelling. Avatar took us to another planet and another perception of reality, all the while being an allegorical tale of ecological care vs. abuse. Somewhere along the way, sometime in your life, I’ll bet you’ve been fascinated by a different perspective, whether presented to you through a book, a documentary, a sermon, a play, a film or a conversation. What did you learn from that encounter? How did it change you, or help shape your perspective? And what is your favourite “escape”: Films, books, visual arts, or music? Please comment below!