Today’s everyday phrases can come in handy when you’re in a tight spot, avoiding danger, or reaching your goal (land ho!) Chockablock came in handy for me last week, as it described how I felt after having been sick for nearly two months (Covid into bronchitis, joy), and then catching up with all those little things in our household that had gone undone. Anyone who’s been married for any length of time will know that spouses tend to take over specific jobs – whether that’s carrying out the rubbish or doing the laundry, cleaning drains or watering plants. I’ll let you guess which jobs are whose. Catching up with those undone jobs stemmed the tide of accumulating chores, and helped me get our home back to shipshape and in Bristol fashion! So enjoy these phrases, and please share in the comments which ones apply to your life!

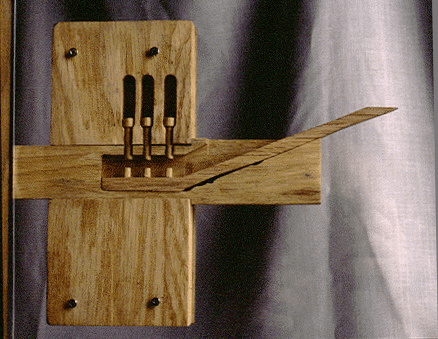

Chockablock: Jam-packed; overcrowded; completely filled, stuffed, or jammed tightly together. You may have heard the term block and tackle; This refers to a system in which a rope, chain or cable (= tackle) is passed over pulleys enclosed in two or more blocks, one fixed and one attached to a load (see image). When these blocks are pulled so close together that no further movement is possible, this is known as being chockablock (this is the usual spelling, which illustrates its meaning perfectly – no space, not even a dash between words!).

Stem the Tide: Try to prevent a situation from becoming worse than it already is. Nautically, it means to tack (steer) against the tide or oncoming storm to avoid being blown off course or capsized.

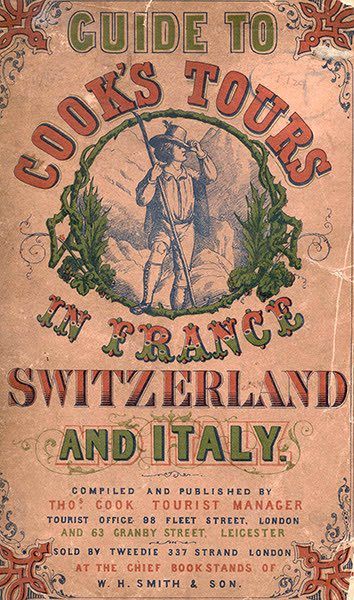

To be Shanghaied: A city in China, Shanghai implied a long voyage (just as Switzerland today implies neutrality in the collective conscious). When landsmen were impressed (volunteered against their will) into the British or American navies in the days of wooden ships of sail, to be Shanghaied meant to be impressed and sent away from home for a long time or extended voyage (not necessarily to China!).

Limey: Shortened slang for “lime juicer”, referring to the English naval ships and the practice of carrying barrels of limes or lime juice to ward off scurvy on long voyages. As the British navy was a dominant force on the seas, the term gradually came to mean British.

Shipshape (and in Bristol Fashion): Everything is okay and in good order. Bristol was, at one point, Britain’s main west coast port; the idiom was used to describe everything being in order with cargo and at the port.

Give a Wide Berth: Leave space for, veer around. Even when a ship is at anchor, it will move with the tide and wind, so the berth, or a docking space, for a ship needs to be ample for a safe mooring. The modern phrase still denotes the danger of steering too close to an unpredictable situation.

Loose Cannon: Unpredictable danger (can be said of a person or situation). When a cannon or a cannonball broke free from its mooring, it created a hazardous situation as it rolled around or across the deck during a storm or in battle.

Port, Starboard: This simple explanation is that these are left and right, respectively, on any ship or airplane. But simple is a bit boring! Buckle up: In the past, as today, the majority of people were right-handed; ships of sail had rudders centred on the stern (back of the ship), but the steering oar came up onto the quarter deck through the right side of the stern. This leads us to the term starboard: Old English steorbord literally meant steer-board, the side on which a vessel was steered.

When pulling into a port, as the steering oar was on the right side, they would anchor starboard out, port in. The port, the left side of the ship as seen from the stern facing forward toward the bow, was formerly known as larboard, from Middle English ladde-borde, meaning loading board (side); it was eventually renamed as the similarity to starboard was confusing in the loud life aboard.

Most airplanes follow this tradition today, with boarding being on the left (port) side. In fact, jet bridges are designed to match the left side of the plane, so unless you are climbing into a grasshopper flight on a remote island, you will board port side!

Ahoy: Used to hail a ship, a boat or a person, or to attract attention. Used today as a humorous warning of impending danger or inconvenience.

Land Ho: To call out “Land ho!” was to let the crew know that land had been spotted. It is a way to let everyone know that the end of a voyage is imminent.