Euphemisms: Stupidity

Euphemisms… we use them daily, whether we realize it or not. They abound in English, multiplying like rabbits in every dark corner of life. In fact, they hardly ever multiply in the sunny spots, because we don’t require them there. The very definition of the word confirms that notion: “The use of a word or phrase to replace another with one that is considered less offensive, blunt or vulgar than the word or phrase which it replaces.”

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.

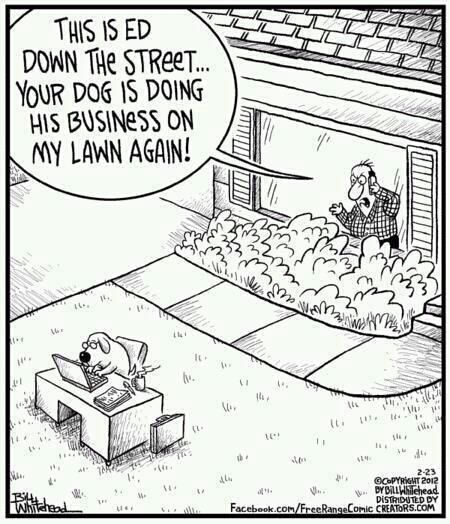

Recently, my husband and I were talking about the topic, and the specifics of the word stupid came up; so without further ado, here’s a round-up of ways of getting around describing someone as stupid, dumb, or, well, an ass:

- Thick as a post

- Doesn’t have both oars in the water

- Two sandwiches shy of a picnic

- A beer short of a six-pack

- A brick short of a load

- A pickle short of a barrel

- Has delusions of adequacy

- Has a leak in their think-tank

- Not the sharpest knife in the drawer

- Not the sharpest tack in the box

- Not the sharpest pencil in the box

- Not the sharpest tool in the shed

- His belt doesn’t go through all the loops

- His cheese has slipped off his cracker

- The light’s on but nobody’s home

- If you stand close enough to them, you’d hear the ocean

- Mind like a rubber bear trap

- Would be out of their depth in a mud puddle

- Their elevator is stuck between two floors

- They’re not tied to the pier

- One prop short of a plane

- Off his rocker

- Not the brightest light in the harbour

- Not the brightest bulb in the pack

- Has a few loose screws

- So dense, light bends around them

- Their elevator/lift doesn’t reach the top floor

- Dumber than a bag of rocks

- Dumber than a hammer

- Fell out of the family tree

- Doesn’t have all the dots on his dice

- As slow as molasses in winter

- As smart as bait

- Has an intellect only rivalled by garden tools

- A few clowns short of a circus

- Silly as a goose

- Addlepated

- Dunderheaded

- A few peas short of a casserole

- Isn’t playing with a full deck of cards

- Has lost his marbles / isn’t playing with all his marbles

- Has bats in his belfry

- A dim bulb

- He’s got cobwebs in his attic

- Couldn’t think his way out of a paper bag

- Fell out of the Stupid Tree and hit every branch on the way down

- If brains were dynamite, he couldn’t blow his nose

I’m sure there are dozens more! If you know of any that haven’t made this list, please put them in a comment below!

Filed under Articles, Etymology, Grammar, History, History Undusted, Humor, Lists, Musings, Quotes, Translations

History Undusted: The Deaf Princess Nun

Princess Alice of Battenberg, christened Victoria Alice Elizabeth Julia Marie (born 25 February 1885 at Windsor Castle, and died 5 December 1969 at Buckingham Palace), later Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, was considered the most beautiful princess in Europe. She was born completely deaf, yet learned to read lips at a young age and could speak several languages. Alice grew up in Germany, and was the great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria. In a time when royalty had little to do with the commoners, she was an unconventional royal who placed the importance of people over privilege and wealth. She was devoted to helping others, and in the turmoil of her own personal life never lost sight of her devotion to God and her commitment to helping those less fortunate.

Princess Alice of Battenberg, christened Victoria Alice Elizabeth Julia Marie (born 25 February 1885 at Windsor Castle, and died 5 December 1969 at Buckingham Palace), later Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, was considered the most beautiful princess in Europe. She was born completely deaf, yet learned to read lips at a young age and could speak several languages. Alice grew up in Germany, and was the great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria. In a time when royalty had little to do with the commoners, she was an unconventional royal who placed the importance of people over privilege and wealth. She was devoted to helping others, and in the turmoil of her own personal life never lost sight of her devotion to God and her commitment to helping those less fortunate.

At the age of 17 she fell in love with Prince Andrew of Greece, and they were married in 1903. They had four daughters and one son; their daughters went on to marry German princes, and their son Prince Philip married Elizabeth II, Queen of England; Alice was therefore the grandmother of the Princes Charles, Andrew, Edward and Princess Anne. She and her family lived in Greece until political turmoil caused the royals to flee into exile in 1917, when they settled in a suburb of Paris. Alice began working with charities helping Greek refugees, while her husband left her and the children for a life of debauchery and gambling in Monte Carlo. She found strength in her Greek Orthodox faith, yet relied on the charity of wealthy relatives in that period of her life when she had no home to call her own, and no husband to help raise her children. Understandably through the stress of circumstances, she had a nervous breakdown in 1930; dubiously diagnosed with schizophrenia, she was committed suddenly and against her will, by her own mother, to a mental institution in Switzerland, without even the chance to say goodbye to her children (Prince Philip, 9 at the time, returned from a picnic to find his mother gone). She continually defended her sanity and tried to leave the asylum. Finally in 1932 she was released, but in the interim her four daughters had married (she had thus been unable to attend their weddings), and Philip had been sent to England to live with his Mountbatten uncles and his grandmother, the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven. As you can imagine, the stress of such treatment did wear on her mental stability, but she was used to being misunderstood, even within her own family, so she decided to get on with her own life.

Alice eventually returned to Athens, living in a small flat and devoting her life to helping the poor. World War II was a personal dilemma for her as her four sons-in-law fought on the German side as Nazi officers, while her son was in the British Royal Navy; yet in her home she hid a Jewish family safely for the duration of the war. She also remained in Athens for the duration of the war, rather than fleeing to relative safety in South Africa, as many of the Greek royal family members did at the time. She worked for the Red Cross in soup kitchens, and used her royal status to fly out for medical supplies, as well as organized orphanages and a nursing circuit for the poor. She continually frustrated well-meaning relatives who sent her food packages by giving the food to the poor, though she had little to live on herself. The German occupied forces assumed she was pro-German due to her ties to royal German commanders, and when a visiting German general asked her if he could do anything for her, she replied, “You can take your troops out of my country.” [For an interesting film on this period in Greek history, see “Captain Corelli’s Mandolin” (2001), starring Nicholas Cage and Penelope Cruz.]

After the war ended, Alice went on to take the example of her aunt, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna (who had been formulating plans for the foundation of a religious order in 1908 when Alice met her in Russia at a family wedding), and founded a religious order, the Christian Sisterhood of Martha and Mary, becoming a nun (though she still enjoyed smoking and playing cards) and establishing a convent and orphanage in a poverty-stricken part of Athens. Her habit consisted of a drab gray robe, white wimple, cord and rosary beads.

Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh with his mother, Princess Alice (taken late 1950s, early 1960s)

In 1967, following another Greek political coup, she travelled to England, where she lived with her son Prince Philip and her daughter-in-law, Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace until her death in 1969. Her final request was to be buried near her sainted aunt in Jerusalem; she was instead initially buried in the royal crypt at Windsor Castle, but in 1988 she was at last interred near her aunt in the Convent of Saint Mary Magdalene on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

In October of 1994 her two surviving children, the Duke of Edinburgh and the Princess George of Hanover, went to the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem to see their mother honoured as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations” for having hidden Jews in her house in Athens during the Second World War. Prince Philip said of his mother’s actions, “I suspect that it never occurred to her that her action was in any way special. She was a person with a deep religious faith, and she would have considered it to be a perfectly natural human reaction to fellow beings in distress.” In 2010 the Princess was posthumously named a Hero of the Holocaust by the British Government.

Information Sources: Wikipedia; The Accidental Talmudist

Originally posted on History Undusted, September 2015

Filed under History, History Undusted, Links to External Articles, Military History

Design Undusted: Norman Doors

You have all come in contact with a Norman Door, even if you might not have known that’s what it was called. Remember the last time you tried to go through a push door by pulling on it? That’s a Norman Door. The name comes from Donald Norman who, after spending time in the UK, wrote a book called, “The Psychology of Everyday Things“, later changed to, “The Design of Everyday Things“. Doors are a prevalent example: Every building has them, but they are not necessarily put through any stringent tests of user-friendliness; if the hinges are hung straight, and the door swings one way or the other, that’s usually enough to pass. Donald Norman’s point is that if people are using a product the wrong way, it’s not their fault – it’s poorly designed. He popularized the term “user-centred design” – designs based on the needs of the users, whoever and however many they might be. Below are a few examples of failed designs – either inconvenient to use or just downright impossible. Next time you come across an object with poor usability, you’ll at least know what to call it.

Filed under Articles, History Undusted, Images, Science & Technology, Videos

Nature Undusted: Magnetic (Gravity) Hills

When I was growing up, I went to a place called Silver Dollar City (in Branson, Missouri) several times; it is a family amusement park with rides and various attractions. One of my favourite attractions was a house that played with your mind: It had water running up a drain, floors that tilted at different angles from room to room, and optical illusions that played with proportions and directions in your perceptions. You simply couldn’t trust what you felt or saw while in that house, and when you came out, it took a minute or two to right your bearings again.

But did you know that there are natural anomalies? Throughout the world, there are areas known as magnetic hills, magic roads or gravity hills. Due to the surrounding geography, the road or stream may appear to be going uphill, when in fact it’s going downhill; this makes water look like it’s flowing upward, or cars in neutral appear to be defying gravity by rolling uphill. It’s nothing more than an optical illusion, but such places attract visitors, the curious and the thrill-seekers.

Wikipedia has a list of over a hundred recognized places; chances are, there might be one near you.

To see the phenomena, click on this link to a short YouTube video about New Brunswick, Canada and the history of what was first known as “Fool’s Hill”.

Filed under Articles, History Undusted, Links to External Articles, Nature, Science & Technology, Videos

So Many Projects, So Little Time…

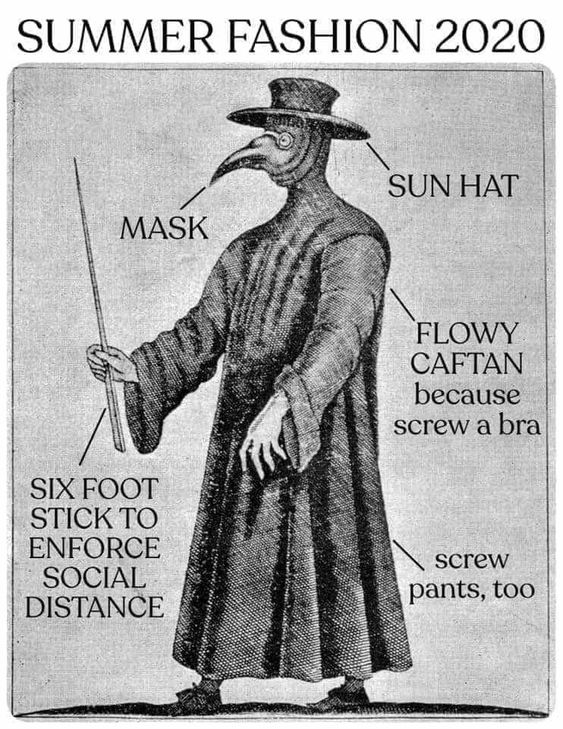

I feel like I’ve been gone for ages – and I guess I have! With the world on hold through lockdown, more than just our social calendar seems to have been turned topsy-turvy. I’m sure I’m not alone in that, but it seems like a lot of routines, such as writing weekly blogs, went on hold as we tried to get our lives back on track through the time of lockdown, of switching to home-office and the changed schedules that brought with it. On one hand, I seemed to have more time on my hands (what with our social agendas being cancelled wholesale), but on the other hand, projects that had been put off wanted tackling. Lockdown is the perfect time to do things like clean out the cellar or deal with household repairs.

One thing I tackled was my craft room: I do a lot of crafts, and I also help people do crafts for projects – whether it’s a personal gift they want to make but don’t know how, or stage props, or repairs to jewellery or baby albums, or making the table settings for celebration dinner parties or anything in between. Because of that, I have a good supply of most supplies I might need. I also do a lot of upcycling crafts – aka tons of plastics, metals, etc. All of that requires space. It went from this…

…to this:

Everything in the cupboard and to the right of it was made in the past 3 weeks. The employees at our local grocery store got used to me raiding their cardboard stacks on my weekly shopping trips! All of the material used was free; to decorate, I used old wrapping papers, magazine pages, old craft book pages, outdated maps, brochures and old music sheets. Handles were made out of everything from old jewellery to cardboard to bottle caps. The boxes atop the dresser (below) were made previously, using beer advent calendar boxes (my husband got the beer, I got the boxes – win-win!).

Now that that sizeable project is done, I’m looking forward to getting back into a full writing rhythm, including blogs! I apologize for my long silence, but as you can see, it wasn’t idle time. While working on paper maché, I was percolating ideas for both my novel and for interesting topics to investigate for this blog – so keep your eyes on this space – there will be more to come soon! 😉

Update: Here are a few updated images of my craft room, which had a facelift in Autumn 2023:

Scandinavian ‘magic sticks’ – yeast logs & yeast rings

Here’s a great little piece of history “undusted”: Have you ever wondered what came before sourdough bread, or why it works? Yeast. And the history behind the symbiotic relationship between humans and that little single-celled microorganism is fascinating.

Likely one of the first organisms domesticated by man, yeast was kept at the ready using many different storage techniques throughout history. One of the oldest such known practices are the Ancient Egyptian yeast breads: delicately baked little loaves of yeasty goodness which, when crumbled into sweet liquid, would create a new yeast starter – for beer, or to leaven bread. For most of man & yeast’s history, bread yeast and beer yeast were the same. The user often had a clear preference, either for keeping the top yeast (barm) or the bottom yeast (lees). But this preference seems more random than geographic, as one farmer would prefer the top, his neighbor the bottom and some would save both – and the yeast would be used for anything that needed fermentation.

A yeast ring made out of sheep vertebrae, Gjærkrans HF-00244 (left photo: Hadeland Folkemuseum) and a teethy straw…

View original post 2,487 more words

Filed under Articles, History, History Undusted, Links to External Articles