In the summer of 2013, I went to Norway on a holiday/research trip for “The Cardinal,” a 2-part fantasy-science fiction novel set in ancient Scotland, ancient Norway, and modern Scotland. Norway, however, seems to carry its dislike of small-talk into the area of promotion and marketing, and as a result, its museums and attractions are not as well advertised, marketed or signposted as they could be; we only found out about this little gem of a site because we happened to run into a Swiss friend in Haugesund, and he knew of the place! I promised the curators to get the word out, so here’ goes, and with pleasure:

On the island of Karmøy, along the western coast of Norway, sits Avaldsnes. With over 50,000 islands in Norway, it wouldn’t seem to our modern minds (as dominated by cars and roads as we are) to be a significant location, but Avaldsnes is rewriting Norse history. It has long been a place from which to control shipping passages through the narrow neck of the Karmunsundet, also called the Seaway to the North, or in Norwegian Nordvegen, and it is the maritime route that eventually gave its name to the country.

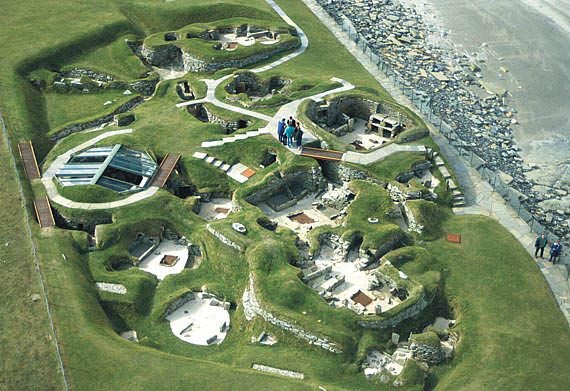

The kings of sagas and lays have become real at Avaldsnes, the rich archaeological finds there making it one of the most important locations in Europe for the study of Viking and Norse history. Avaldsnes was a royal seat, so it’s not surprising that some of the most important burials in Norway have been found here: One of its ship burials was dated to the 8th century (making it much older than any other such burials known of thus far). It was clearly a king’s burial, and the findings there have proven its political importance several hundred years before King Harald Fairhair unified Norway.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Today there are three main points of interest at Avaldsnes, all within walking distance from each other: St. Olav’s church, built on the site of the oldest church in Norway, was commissioned by King Håkon Håkonson around 1250 AD as part of the royal manor complex. On the north side of the church stands the Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle, one of Norway’s tallest standing stones, measuring in at 7.2 metres today (though it was originally much taller; it can be seen in the picture above): Local legend says that when the obelisk touches the wall of the church, Doomsday will come; over the years, priests have climbed the stone in the dead of night to chip away any threatening pieces from the top, thus saving the world from annihilation. This church was an important site for pilgrims on their way to Nidaros (the medieval name for Trondheim, the capital of the land’s first Christian kings and the centre of Norwegian spiritual life up until the Protestant Reformation); on the north side of the church is a sealed door which was originally the entrance for those pilgrims, as it is said that they had to enter any church with their backs to the north.

The next site is the Nordvegen Historic Centre; at first glance, it’s merely a circular stone monument, but it is actually a stairway leading down into the underground museum, built so as to not interfere with the landscape. The exhibitions guide you (with a bit of modern technology) through 3,500 years of history through Avaldsnes, focusing on daily life, international contacts and cultural influences from those contacts. Foreign trade and communication were major factors at Avaldsnes, and archaeological evidence shows it to be a barometer to the prosperity and decline of European commerce as a whole. The museum has a hands-on section, as well as a gift shop that’s well-stocked with books covering various aspects of Viking history.

The third site is a hidden gem, located about 20 minutes’ walk from St. Olav’s: The Viking farm. The gravel path takes you along the shore, over two bridges and through a forest to a small island. It’s well worth the hike, as you come through the forest to find a Viking village tucked behind a typical Telemark-style fence (pictured above). A 25-metre longhouse is the centrepiece, a reconstruction of a 950 AD house, and built of pine and oak, with windows of mica sheets. The aroma of tar wafts from the house as you approach, as it is painted with pitch to weatherproof it; the smell reminds me of a dark peat-whiskey, and also of Stave churches, which are also painted with the tar. [The photo of the longhouse has one element missing to the trained eye: The low stone wall which should surround the house, as insulation, is missing at the moment while boards are being repaired.] Other buildings on the farm include pit houses (both woven twig walls as well as wattle and daub) used for activities such as weaving, cooking or food preparation, and other crafts necessary to daily life; a round house, a reconstruction of archaeological finds in Stavanger (which may be a missing link between temples and stave churches in their construction); various buildings of a smaller size; and at the shore is a 32-metre leidang boat house, representing a part of the naval defence system developed in the Viking Age: A settlement with a leidang was expected to man the ship with warriors and weapons when the king called upon them for aid. When the boat house was vacant of its ship it was used as a feasting hall, and the modern replica follows that example as it is often hired out for celebrations or festivals.

Both the museum and the Viking farm have friendly and knowledgeable staff; the farm staff are all in hand-made period clothing and shoes; as a matter of fact, one of the women was working on her dress while we were there, and she said it was linen; the total hours to make such a dress from start to finish would be around 600 hours (including shearing, spinning, weaving, then cutting and sewing). Had it been made of or included leather, it would have taken much, much longer. That is why clothing was very valuable, and most people only had the clothes on their back; you were considered fortunate, and even wealthy, if you had a change of clothing – even into the mid-eighteenth century in countries such as England.

If you are interested in Viking history, Avaldsnes is well worth the journey. Take your time; we stayed overnight in the area to spread the visit out over two days, and we could have spent much more time there. If you’re a natural introvert like me, you’ll need time to process the multitude of impressions, but that’s what we like – quality time, and quality input. And then get the word out about these points of interest!

Originally posted on History Undusted, 14 September 2013

Skara Brae

Skara Brae If you get a chance to go, do so; take at least a fortnight on Mainland

If you get a chance to go, do so; take at least a fortnight on Mainland