WikiCells – Edible wrapping coming soon!

“What this power is I cannot say; all I know is that it exists and it becomes available only when a man is in that state of mind in which he knows exactly what he wants and is fully determined not to quit until he finds it.”

Alexander Graham Bell

Most inventions are the results of exploration, experimentation, blood, sweat and tears, and lots of sleepless nights. But there are some moments of serendipity, those “Hmm. That’s strange…” discoveries that are not lightly tossed aside but seen for their potential. It’s taking the lemons life has thrown their way, tossing in a wet rag and a few copper and zinc coins, and coming up with a battery.

Here’s a line-up of a few of those wet rag-tossers of edible discoveries:

Coke

Who: John Pemberton, pharmacist, Colonel of the Confederate Army wounded in the Battle of Columbus, Georgia.

When: 1886

Why: Like so many wounded war veterans of his time, he had become addicted to morphine to handle the pain. Being a pharmacist, he wanted to find a cure for the addiction. Inadvertently, he ended up inventing what has became another addiction for untold millions: Coca-Cola. And like many elixirs of the time, his was touted as “a valuable brain tonic” that would relieve exhaustion, calm nerves and cure headaches. But sadly, Pemberton died two years later and never saw his medicinal mixture give birth to the soft drink empire.

Saccharin

Who: Constantin Fahlberg, unhygienic chemist.

When: 1879

Why: He’d been trying to find ways to use coal tar; he went home for dinner, and noticed that his wife’s bread rolls were unusually sweet; no, she hadn’t changed her recipe – he just hadn’t washed his hands before eating. He went back to his lab and taste-tested until he found the sweet source. That’s just gross.

Cornflakes Cereal

Who: William Keith Kellogg, assisting his brother, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, the superintendent of The Battle Creek Sanatarium in Michigan.

When: 1895

Why: One day while making bread dough with boiled wheat, he left it sitting while he helped his brother and when he returned to roll out the dough, it came out flaky. He decided to bake it anyway, creating a crunchy and flaky snack. It was a huge hit with the patients, and so he set out to manufacture it on a larger, and more intentional, scale. He switched to using corn and launched the “Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flakes Company” in 1906; eventually he realized that his name was more catchy.

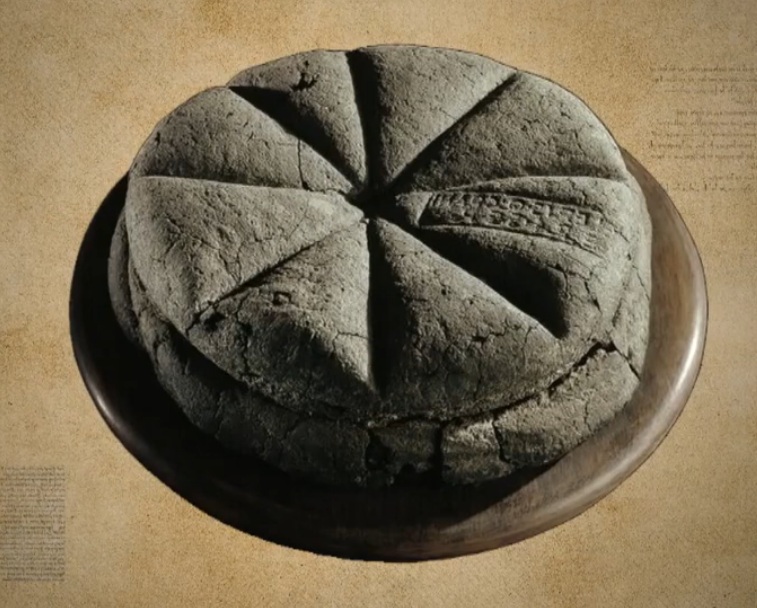

Brandy

Who: An intrepid soul.

When: Around the 12th Century

Why: Concentrated alcoholic beverages have been around probably as long as alcohol has been transported; by evaporating the water from wine, it was more stable for transportation, and then reconstituted at the other end. At some point someone decided to skip the rehydration phase and just go for it, and brandy (“burnt wine” – in the distillation process, a portion was lit to test the purity) was born.

Potato chips

Who: George Crum, Chef in Saratoga Springs, New York.

When: 1853

Why: The usual story says that he was trying to please an unhappy, picky customer; after several complaints that the potato was not thin enough or cooked enough, he sliced them paper-thin and fried them to a crisp. The customer loved them, and the name “Saratoga Chips” persisted until the mid-20th century.

Chocolate Chip Cookies

Who: Mrs. Ruth Graves Wakefield, owner of the Toll House Inn, in Whitman, Massachusetts.

When: 1930

Why: While making cookies one day, she ran out of regular baker’s chocolate and substituted broken pieces of semi-sweet chocolate, thinking they would melt into the batter. They didn’t, and chocolate chips were born. She sold the recipe to Nestle in exchange for a lifetime supply of chocolate chips (rather than patenting it and making millions!). Every bag of Nestle chocolate chips in America has a variation of her original recipe printed on the packaging.

Popsicles

Who: Frank Epperson, 11 years old at the time, of Oakland, California.

When: 1905

Why: He left a mixture of powdered soda and water out on the porch, which happened to have a stir stick in it; that night the temperatures reached a record low, and the next morning he discovered his frozen fruit-flavoured drink; the “Epsicle” was born. 18 years later he patented that little Eureka moment, and the Popsicle became intentional.

Chewing Gum

Who: Thomas Adams

When: 1870

Why: Chewing gum has actually been around for over 5,000 years; Neolithic tribes used various tree saps, and the Aztecs used chicle as a basis for a gum-like substance. But they didn’t patent it and market it. So along came Thomas Adams: Given a supply of chicle from Mexico, his original intention was to use it as a rubber substitute; it failed in that capacity, but instead he cut it into strips and marketed it as “Adams New York Chewing Gum” in 1871, becoming the first mass-produced chewing gum in the world.

Ice Cream Cones

Who: The modern, mechanized version: Frederick Bruckman, 1912

When: 1912

Why: Edible cones, made from little waffles rolled, were mentioned in French cooking books as early as 1825. Several Americans vie for the title of “Creator of the modern ice cream cone,” but all seem to appear around the same time, the 1904 World’s Fair and shortly thereafter, which tells me someone got the idea from someone, tried to patent it (unsuccessfully) and everyone else jumped on the idea claiming first dibs. But as far as history goes, it’s no new idea – just necessity being the mother of invention. Frederick Bruckman is credited with the modern ice cream cone, as he invented a machine for rolling them.

Champagne

Who: Ah. Now that’s a simple question with a thorny answer. Not a French Benedictine Monk (Dom Pérignon); in reality, he did everything he could to make the wine less sparkly because it kept exploding in his winery. In actual fact it was the English who recognized the added value of bubbly wine, exploding bottles and all. The first to recognize the process, document it, and enjoy it, was Christopher Merret, English scientist.

When: 1662

Why: Merret “was born in Gloucestershire in either 1614 or 1615 (the Champagne seems to have clouded his memory), studied at Oxford (a notorious training ground for heavy drinkers), and in 1661 translated and expanded an Italian treatise on bottle manufacture. It seems to be this that drew his attention to the question of exploding Champagne, because the following year he published a paper entitled ‘Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines’. In this, he tried to explain why wine became bubbly, and identified the second fermentation in the bottle as the main cause. He also described adding sugar or molasses to wine to bring on this second fermentation deliberately. Sparkliness was a positive thing, Merret said, and could be produced in any wine, particularly now that England was making bottles that were capable of holding in the bubbles. Thus, while Dom Pérignon was trying to do away with the fizz, the Brits wanted more.” [1000 Years of Annoying the French (pp. 179-180). Random House UK. Kindle Edition.]

Sandwiches

Who: Just about everyone except John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, an 18th-century English aristocrat.

When: from the 18th century known as a “sandwich;” from antiquity and various cultures from before history began to be recorded.

Why: In the 1700s, the Earl of Sandwich was often too busy to sit down for a proper meal, so he had his servants bring his meat placed between slices of bread to avoid greasy fingers from handling the meat directly. People began asking for “the same as Sandwich.” Throughout Asia, Africa, and South America, flatbread has long been used to scoop food from plate to mouth (as cutlery had not yet been invented, or was not widespread). Those aristocrats could have very easily asked for “the same as savages,” and we would thus be eating savages today. Cannibalistic, if you ask me…

Liquorice Allsorts

Who: Charlie Thompson, a sales representative of Geo. Bassett & Co.

When: 1899

Why: Charlie supposedly dropped a tray of samples he was showing a client in Leicester, mixing up the various sweets. He scrambled to re-arrange them, and the client loved the bright mix of colours and shapes, and Allsorts hit the shelves soon after.

Crepe Suzette

Who: Disputed; reputed to be fourteen year-old assistant waiter Henri Charpentier, at the Maitre at Monte Carlo’s Café de Paris.

When: 1895

Why: Preparing desert for the English Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII), Henri accidentally caught the cordial of the crepe on fire. Rather than start over he tasted it and thought it delicious, so he served it; the Prince asked for the dish to be named for one of his companions, Suzette (as Crepe in French is feminine, rather than masculine).

Worcestershire sauce

Who: John Wheeley Lea and William Henry Perrins, British chemists.

When: 1837

Why: The story goes that someone asked them to attempt a recipe for curry powder; they tried, and made it liquid; it was far too strong to be palatable, so they put it in a cellar barrel for a few years. Looking to make space, they were going to dispense with the offensive product, but tried it again and found that it had fermented and become milder, and actually quite good thank you. They began to market it, and it became a success.

Kool-Aid

Who: Edwin Perkins, innovator and entrepreneur, Hastings, Nebraska.

When: 1927

Why: Perkins’ father opened a general store in town where the boy was introduced to new and exciting food products such as Jell-O. One of the company’s offerings that proved most popular was a concentrated drink mix called Fruit Smack, which came in six flavours. A four-ounce bottle made enough for an entire family to enjoy at an affordable price. But shipping the bottles of syrup was costly and breakage was becoming a problem. In 1927 this prompted him to develop a method of removing the liquid from Fruit Smack so the residual powder could be re-packaged in envelopes; consumers would then only have to add water to enjoy the drink at home. Perkins designed and printed envelopes with a new name —Kool Ade —to package the powder with (later this spelling would change to “Kool-Aid”). Because the packets were lightweight, shipping costs dropped; Perkins sold each Kool-Aid packet for a dime, wholesale by mail at first, to grocery, candy and other stores. By 1929, Kool-Aid was a nation-wide product.

Life Savers Candy

Who: Clarence Crane (Cleveland, Ohio), chocolate manufacturer

When: 1912

Why: During the summer of 1912, Mr. Crane invented a “summer candy” that could withstand heat better than chocolate. Since the mints looked like miniature life preservers, he called them Life Savers. After registering the trademark, Crane sold the rights to the peppermint candy to Edward Noble for $2,900. Noble created tin-foil wrappers to keep the mints fresh, instead of cardboard rolls. Pep-O-Mint was the first Life Saver flavour. Since then, many different flavours of Life Savers have been produced. The five-flavour roll first appeared in 1935.