Last Sunday at church, a friend filled an entire room with her late father’s books, setting up an impromptu book shop. I chose several books, most of which are in Fraktur typeface, known to some people as “Gothic” or “Old German”. I enjoy reading such books because they offer a snapshot of a cultural way of thinking. The books I chose were printed between 1877 and 1940. The latter date is significant, as you’ll soon see.

First of all, let’s clarify a few terms: Though many people think of font and typeface as interchangeable, in fact, they refer to two different aspects of a writing style. Typeface refers to a particular style of lettering (e.g. Times New Roman), while font refers to the variations within that style, such as size and weight (CAPS, bold, italic, etc.). Another term we know but may not fully understand is Serif: This refers to the small stroke or line attached to the larger stroke of a letter; an example would be an A with “feet” at the bottom of each down-stroke. Sans Serif simply means “without Serif”.

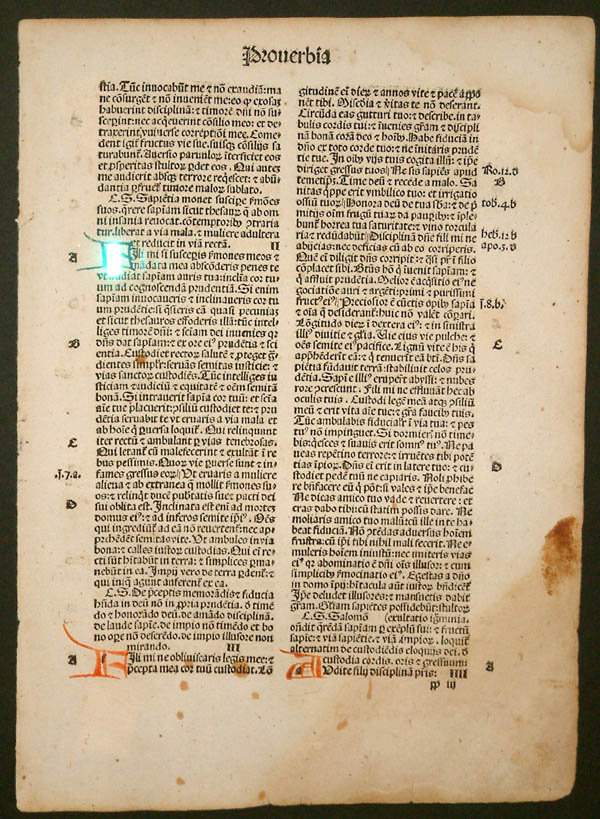

The first moveable-type printing press, designed by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany around 1440, was based on the ancient Roman design of a screw press used to press wine or oil, which in turn went on to be used to press designs into cloths. He was likely familiar with intaglio printing and may have done some work himself in copper engraving. These designs and uses likely fermented in his inventor’s mind into what became the revolutionary turning point of literacy. Gutenberg’s original typeface was called Donatus-Kalender; the metal type design was itself a form of Textura (more on that in a moment).

This original family of typefaces was known as “Blackletter”, aka “Gothic scripts”, with the height of popularity peaking around the 14th to 15th centuries. The ancestor of the Blackletter was called the Carolingian minuscule, a calligraphic standard of handwriting widely used in the medieval period, when literacy began increasing and a need for books in a wide range of subjects began to be in demand. It is thought to have been developed in the mid-770s by Benedictine monks north of Paris in the Corbie Abbey, famous for its scriptorium and library. The minuscule itself was derived from Roman Uncial as well as Irish Insular script, which was developed in Irish monasteries and spread throughout Europe.

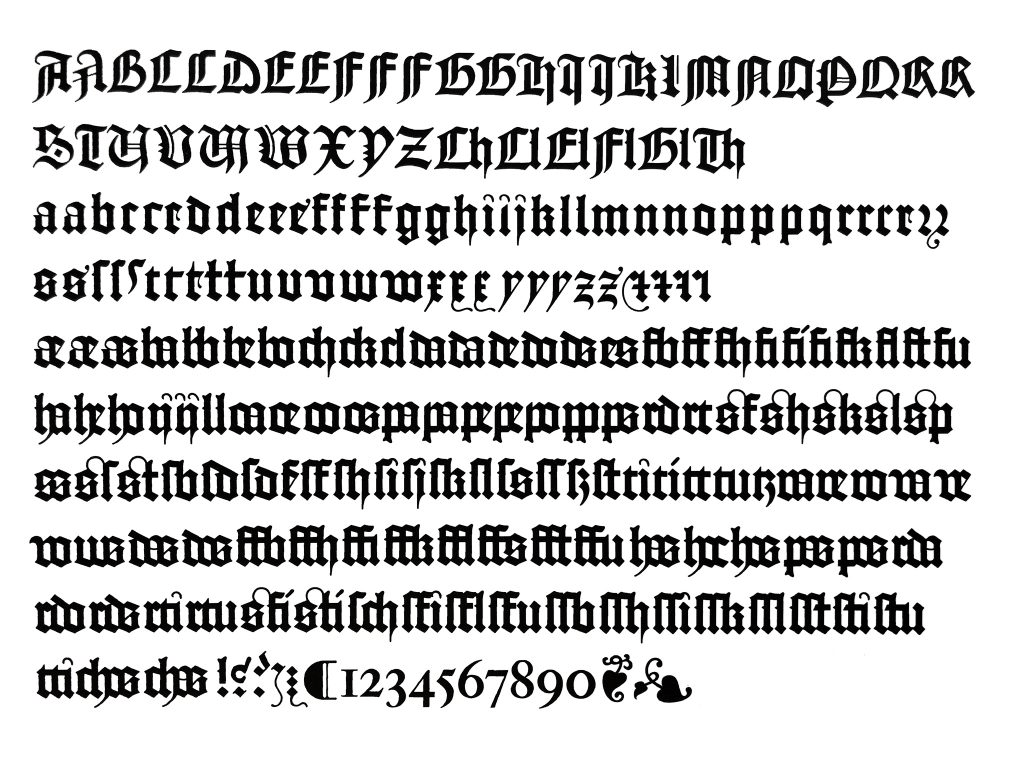

The family of Blackletter typefaces included Early Gothic, which was a transitional script between the Carolingian miniscule and Textura (the most calligraphic form of Blackletter); Schwabacher was a form popular in early German print typefaces (it became widely known with the spread of Luther Bibles from 1522), in use from the 15th century until it was eventually replaced by Fraktur around 1530, though it was still used alongside Fraktur for emphasis, much like we use bold or italic today.

Another blackletter typeface developed between 1470 and 1600: Antiqua. This typeface’s letters were designed to look like the handwriting of ancient Roman documents, with the letters flowing together, strokes connecting them in a continuous line, whereas Fraktur was distinguished by having letters “fractured” – separate from one another. The Antiqua-Fraktur Dispute deserves its own article, so stay tuned!

The Habsburg Emperor Maximillian I (1459-1519) was King of the Romans* from 1486 to 1519 [the title of king was used by the kings of East Francia, the territory later referred to as the Kingdom of Germany, from the time of Henry II (1002) to Joseph II (1764)]. The king commissioned the artist Albrecht Dürer to create a series of woodcut engravings of the Triumphal Arch [Though many are familiar with the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, it is only one example of this ancient Roman architectural feature used as a free-standing structure (rather than the Greek version, which was used within a structure such as a temple).]. These engravings would be used to create what we would recognize today as essentially wallpaper, though its purpose was more of a statement of power or propaganda (read personal marketing) commemorating his nobility, generosity, and military conquests – an incongruous combination, if you ask those conquered… The final composite of printed papers stood nearly 3 metres (12 feet) high and was only one part of a series of three enormous prints commissioned by the king.

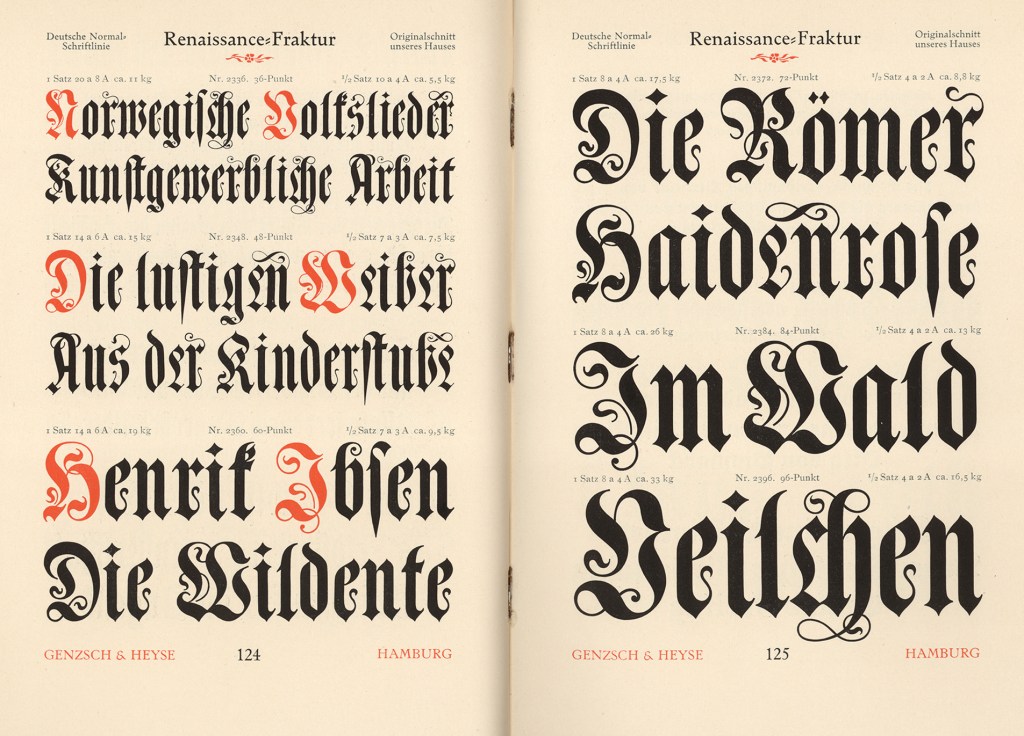

The Fraktur typeface was designed in the 1530s by Hieronymus Andreae, a German woodblock cutter, printer, publisher, and typographer closely connected to Albrecht Dürer. The typeface was made to decorate the arch, telling the stories of the figures depicted throughout. The typeface became popular in Europe and was in use in the German-speaking world, as well as areas under its influence (Scandinavia, Central Europe, and some eastern European regions), into the 20th century. Specifically, Fraktur was in use in German until 1941, when it was actually banned (which places one of the books I purchased on Sunday within one year of the end of the era of Fraktur!). The atmosphere that led to that ban arose from the dispute mentioned above. Once the Nazis were defeated, the ban was lifted, but Fraktur never regained its widespread popularity after that, though you can still see it occasionally in pub signs or various forms of ads, like beer brands.

I just pulled two books from my library shelves: One is an English book originally printed in 1895, with my book being printed in 1915; the other is a German book printed in 1892. The typefaces are widely different: The English text likely used the French Oldstyle, while the German book uses Renaissance Fraktur for the text body, while the end pages act as indexes and use a variety of blackletter typefaces, such as Muenchner Fraktur, Antike Kanzlei, and Enge verzierte Altdeutsch. To see examples of the typefaces mentioned here, please click on the link for Fonts In Use.

I hope you enjoyed this jaunt through history! Nearly every name mentioned, every typeface, and every event deserves its own undusting. Next time, we’ll deep-dive into the dispute that lasted well over a century!