Nautical Jargon

In the course of writing novels, I do a lot – I mean a LOT – of research. And in the course of doing that LOT of research I come across interesting bits and bobs that I glean, putting into files on my computer for reference and rainy days. So it was that I came across a digitalized version of the 1867 “The Sailor’s Word-Book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms, including some more especially military and scientific, but useful to seamen; as well as archaisms of early voyagers, etc. by the late ADMIRAL W. H. SMYTH, K.S.F., D.C.L., &c.” I love the fact that antique books had entire blurbs built into their titles! The document itself translates into no less than 586 pages in a word document; obviously I won’t force that upon you. But I will give you a snippet of words from A to Z that have an Anglo-Saxon origin or influence. If you’re interested in even more such lists broken down from the book, check out my “History Undusted” blog here. But first, here’s a snatch from the preface, written by the late Admiral W.H.Smyth:

“This predilection for sea idiom is assuredly proper in a maritime people, especially as many of the phrases are at once graphic, terse, and perspicuous. How could the whereabouts of an aching tooth be better pointed out to an operative dentist than Jack’s “‘Tis the aftermost grinder aloft, on the starboard quarter.” The ship expressions preserve many British and Anglo-Saxon words, with their quaint old preterites and telling colloquialisms; and such may require explanation, as well for the youthful aspirant as for the cocoa-nut-headed prelector in nautic lore. It is indeed remarkable how largely that foundation of the English language has been preserved by means of our sailors.

“This phraseology has necessarily been added to from time to time, and consequently bears the stamp of our successive ages of sea-life. In the “ancient and fishlike” terms that brave Raleigh derived from his predecessors, many epithets must have resulted from ardent recollections of home and those at home, for in a ship we find: Apeak, Apron, A-stay, Bonnet, Braces, Bridle, Cap, Catharpins, Cat-heads, Cat’s-paw, Cot, Cradle, Crib, Crow-foot, Crow’s nest, Crown, Diamond, Dog, Driver, Earrings, Eyes, Fox, Garnet, Goose-neck, Goose-wing, Horse, Hose, Hound, Jewel, Lacings, Martingale, Mouse, Nettle, Pins, Puddings, Rabbit, Ribband, Saddle, Sheaves, Sheets, Sheepshank, Shoe, Sister, Stays, Stirrup, Tiller, Truck, Truss, Watch, Whip, Yard.”

Now, on with the show!

A-C

A. The highest class of the excellence of merchant ships on Lloyd’s books, subdivided into A 1 and A 2, after which they descend by the vowels: A 1 being the very best of the first class. Formerly a river-built (Thames) ship took the first rate for 12 years, a Bristol one for 11, and those of the northern ports 10. Some of the out-port built ships keep their rating 6 to 8 years, and inferior ones only 4. But improvements in ship-building, and the large introduction of iron, are now claiming longer life. “A” is an Anglo-Saxonism for in or on; as a‘board, a‘going, &c.

ABORD. An Anglo-Saxon term, meaning across, from shore to shore, of a port or river.

ACUMBA. Oakum. The Anglo-Saxon term for the hards, or the coarse part, of flax or unplucked wool.

ADOWN. The bawl of privateersmen for the crew of a captured vessel to go below. Saxon, adoun.

ÆWUL. An Anglo-Saxon term for a twig basket for catching fish.

AFORE. A Saxon word opposed to abaft, and signifying that part of the ship which lies forward or near the stem. It also means farther forward; as, the galley is afore the bitts.—Afore, the same as before the mast.—Afore the beam, all the field of view from amidship in a right angle to the ship’s keel to the horizon forward.

AFT—a Saxon word contradistinctive of fore, and an abbreviation of abaft—the hinder part of the ship, or that nearest the stern.—Right aft is in a direct line with the keel from the stern.—To haul aft a sheet is to pull on the rope which brings the clue or corner of the sails more in the direction of the stern.—The mast rakes aft when it inclines towards the stern.

AHOO, or All Ahoo, as our Saxon forefathers had it; awry, aslant, lop-sided.

ALLAN. A word from the Saxon, still used in the north to denote a piece of land nearly surrounded by a stream.

ALOFT [Anglo-Saxon, alofte, on high]. Above; overhead; on high. Synonymous with up above the tops, at the mast-head, or anywhere about the higher yards, masts, and rigging of ships.—Aloft there! the hailing of people in the tops.—Away aloft! the command to the people in the rigging to climb to their stations. Also, heaven: “Poor Tom is gone aloft.”

ALONG [Saxon]. Lengthwise.—Alongside, by the side of a ship; side by side.—Lying along, when the wind, being on the beam, presses the ship over to leeward with the press of sail; or, lying along the land.

AMAIN [Saxon a, and mægn, force, strength]. This was the old word to an enemy for “yield,” and was written amayne and almayne. Its literal signification is, with force or vigour, all at once, suddenly; and it is generally used to anything which is moved by a tackle-fall, as “lower amain!” let run at once. When we used to demand the salute in the narrow seas, the lowering of the top-sail was called striking amain, and it was demanded by the wave amain, or brandishing a bright sword to and fro.

ANGIL. An old term for a fishing-hook [from the Anglo-Saxon ongul, for the same]. It means also a red worm used for a bait in angling or fishing.

ATEGAR. The old English hand-dart, named from the Saxon aeton, to fling, and gar, a weapon.

AXE. A large flat edge-tool, for trimming and reducing timber. Also an Anglo-Saxon word for ask, which seamen still adhere to, and it is difficult to say why a word should be thought improper which has descended from our earliest poets; it may have become obsolete, but without absolutely being vulgar or incorrect.

BAT, or Sea-bat. An Anglo-Saxon term for boat or vessel. Also a broad-bodied thoracic fish, with a small head, and distinguished by its large triangular dorsal and anal fins, which exceed the length of the body. It is the Chætodon vespertilio of naturalists.

BAT-SWAIN. An Anglo-Saxon expression for boatswain.

BEACON. [Anglo-Saxon, béacn.] A post or stake erected over a shoal or sand-bank, as a warning to seamen to keep at a distance; also a signal-mark placed on the top of hills, eminences, or buildings near the shore for the safe guidance of shipping.

BECK [the Anglo-Saxon becca]. A small mountain-brook or rivulet, common to all northern dialects. A Gaelic or Manx term for a thwart or bench in the boat.

BLEAK. The Leuciscus alburnus of naturalists, and the fresh-water sprat of Isaak Walton. The name of this fish is from the Anglo-Saxon blican, owing to its shining whiteness—its lustrous scales having long been used in the manufacture of false pearls.

BRAND. The Anglo-Saxon for a burnished sword. A burned device or character, especially that of the broad arrow on government stores, to deface or erase which is felony.

BROKER. Originally a broken tradesman, from the Anglo-Saxon broc, a misfortune; but, in later times, a person who usually transacts the business of negotiating between the merchants and ship-owners respecting cargoes and clearances: he also effects insurances with the underwriters; and while on the one hand he is looked to as to the regularity of the contract, on the other he is expected to make a candid disclosure of all the circumstances which may affect the risk.

BURG [the Anglo-Saxon burh]. A word connected with fortification in German, as in almost all the Teutonic languages of Europe. In Arabic the same term, with the alteration of a letter, burj, signifies primarily a bastion, and by extension any fortified place on a rising ground. This meaning has been retained by all northern nations who have borrowed the word; and we, with the rest, name our towns, once fortified, burghs or boroughs.

BURN, or Bourne. The Anglo-Saxon term for a small stream or brook, originating from springs, and winding through meadows, thus differing from a beck. Shakespeare makes Edgar say in “King Lear”—

CAPTAIN. This title is said to be derived from the eastern military magistrate katapan, meaning “over everything;” but the term capitano was in use among the Italians nearly 200 years before Basilius II. appointed his katapan of Apulia and Calabria, A.D. 984. Hence, the corruption of the Apulian province into capitanata. Among the Anglo-Saxons the captain was schipp-hláford, or ship’s lord. The captain, strictly speaking, is the officer commanding a line-of-battle ship, or a frigate carrying twenty or more cannon. A captain in the royal navy is answerable for any bad conduct in the military government, navigation, and equipment of his ship; also for any neglect of duty in his inferior officers, whose several charges he is appointed to regulate. It is also a title, though incorrectly, given to the masters of all vessels whatever, they having no commissions. It is also applied in the navy itself to the chief sailor of particular gangs of men; in rank, captain of the forecastle, admiral’s coxswain, captain’s coxswain, captain of the hold, captain of main-top, captain of fore-top, &c.

CHESIL. From the Anglo-Saxon word ceosl, still used for a bank or shingle, as that remarkable one connecting the Isle of Portland with the mainland, called the Chesil Beach.

CHIMBE [Anglo-Saxon]. The prominent part or end of the staves, where they project beyond the head of a cask.

CHIULES. The Saxon ships so called.

CLIFF [from the Anglo-Saxon cleof]. A precipitous termination of the land, whatever be the soil.

COGGE. An Anglo-Saxon word for a cock-boat or light yawl, being thus mentioned in Morte Arthure— “Then he covers his cogge, and caches one ankere.” But coggo, as enumerated in an ordinance of parliament (temp. Rich. II.), seems to have been a vessel of burden used to carry troops.

COLMOW. An old word for the sea-mew, derived from the Anglo-Saxon.

CONN, Con, or Cun, as pronounced by seamen. This word is derived from the Anglo-Saxon conne, connan, to know, or be skilful. The pilot of old was skillful, and later the master was selected to conn the ship in action, that is, direct the helmsman. The quarter-master during ordinary watches conns the ship, and stands beside the wheel at the conn, unless close-hauled, when his station is at the weather-side, where he can see the weather-leeches of the sails.

COOMB. The Anglo-Saxon comb; a low place inclosed with hills; a valley. (CWM: CWM, or Comb. A British word signifying an inlet, valley, or low place, where the hilly sides round together in a concave form; the sides of a glyn being, on the contrary, convex.)

CORN, To. A remainder of the Anglo-Saxon ge-cyrned, salted. To preserve meat for a time by salting it slightly.

CRAFT [from the Anglo-Saxon word cræft, a trading vessel]. It is now a general name for lighters, hoys, barges, &c., employed to load or land any goods or stores.—Small craft. The small vessels of war attendant on a fleet, such as cutters, schooners, gunboats, &c., generally commanded by lieutenants. Craft is also a term in sea-phraseology for every kind of vessel, especially for a favourite ship. Also, all manner of nets, lines, hooks, &c., used in fishing.

CROCK [Anglo-Saxon, croca]. An earthen mess-vessel, and the usual vegetables were called crock-herbs. In the Faerie Queene Spenser cites the utensil:— “Therefore the vulgar did aboute him flocke,

Like foolish flies about an honey-crocke.”

CULVER. A Saxon word for pigeon, whence Culver-cliff, Reculvers, &c., from being resorted to by those birds. [Latin, columba; b and v are often interchanged.]

CUTE. Sharp, crafty, apparently from acute; but some insist that it is the Anglo-Saxon word cuth, rather meaning certain, known, or familiar.

D-F

DEL. Saxon for part.—Del a bit, not a bit, a phrase much altered for the worse by those not aware of its antiquity.

DENE. The Anglo-Saxon dæne; implying a kind of hollow or ravine through which a rivulet runs, the banks on either side being studded with trees.

DIGHT [from the Anglo-Saxon diht, arranging or disposing]. Now applied to dressing or preparing for muster; setting things in order.

DREINT. The old word used for drowned, from the Anglo-Saxon.

DRIVE, To [from the Anglo-Saxon dryfan]. A ship drives when her anchor trips or will not hold. She drives to leeward when beyond control of sails or rudder; and if under bare poles, may drive before the wind. Also, to strike home bolts, tree-nails, &c.

DUNES. An Anglo-Saxon word still in use, signifying mounds or ridges of drifted sands.

DYKE. From the Anglo-Saxon dic, a mound or bank; yet in some parts of England the word means a ditch.

EAGRE, or Hygre. The reciprocation of the freshes of various rivers, as for instance the Severn, with the flowing tide, sometimes presenting a formidable surge. The name seems to be from the Anglo-Saxon eágor, water, or Ægir, the Scandinavian god of the sea.

EAST. From the Anglo-Saxon, y’st. One of the cardinal points of the compass. Where the sun rises due east, it makes equal days and nights, as on the equator.

EASTINTUS. From the Saxon, east-tyn, an easterly coast or country. Leg. Edward I.

EBB. The lineal descendant of the Anglo-Saxon ep-flod, meaning the falling reflux of the tide, or its return back from the highest of the flood, full sea, or high water. Also termed sæ-æbbung, sea-ebbing, by our progenitors.

EBBER, or Ebber-shore. From the Anglo-Saxon signifying shallow.

EGG, To. To instigate, incite, provoke, to urge on: from the Anglo-Saxon eggion.

EKE, To. [Anglo-Saxon eácan, to prolong.] To make anything go far by reduction and moderation, as in shortening the allowance of provisions on a voyage unexpectedly tedious.

ENSIGN. [From the Anglo-Saxon segn.] A large flag or banner, hoisted on a long pole erected over the stern, and called the ensign-staff. It is used to distinguish the ships of different nations from each other, as also to characterize the different squadrons of the navy; it was formerly written ancient. Ensign is in the army the title of the junior rank of subaltern officers of infantry; from amongst them are detailed the officers who carry the colours.

ERNE. From the Anglo-Saxon earne, a vulture, a bird of the eagle kind. Now used to denote the sea-eagle.

FARE [Anglo-Saxon, fara]. A voyage or passage by water, or the money paid for such passage. Also, a fishing season for cod; and likewise the cargo of the fishing vessel.

FATHOM [Anglo-Saxon, fædm]. The space of both arms extended. A measure of 6 feet, used in the length of cables, rigging, &c., and to divide the lead (or sounding) lines, for showing the depth of water.—To fathom, is to ascertain the depth of water by sounding. To conjecture an intention.

FELL, To. To cut down timber. To knock down by a heavy blow. Fell is the Anglo-Saxon for a skin or hide.

FIN [Anglo-Saxon, Finn]. A native of Finland; those are Fins who live by fishing. We use the whole for a part, and thus lose the clue which the Fin affords of a race of fishermen.

FIRE-BARE. An old term from the Anglo-Saxon for beacon.

FLOAT [Anglo-Saxon fleot or fleet]. A place where vessels float, as at Northfleet. Also, the inner part of a ship-canal. In wet-docks ships are kept afloat while loading and discharging cargo. Two double gates, having a lock between them, allow the entry and departure of vessels without disturbing the inner level. Also, a raft or quantity of timber fastened together, to be floated along a river by a tide or current.

FOAM [Anglo-Saxon, feám]. The white froth produced by the collision of the waves, or by the bow of a ship when acted on by the wind; and also by their striking against rocks, vessels, or other bodies.

FORE-FINGER, or Index-finger. The pointing finger, which was called shoot-finger by the Anglo-Saxons, from its use in archery, and is now the trigger-finger from its duty in gunnery.

FOTHER [Anglo-Saxon foder]. A burden; a weight of lead equal to 191⁄2 cwts. Leaden pigs for ballast.

FYRDUNG [the Anglo-Saxon fyrd ung, military service]. This appears on our statutes for inflicting a penalty on those who evaded going to war at the king’s command.

G-H

GARE. The Anglo-Saxon for ready.

GAR-FISH. The Belone vulgaris, or bill-fish, the bones of which are green. Also called the guard-fish, but it is from the Anglo-Saxon gar, a weapon.

GEAR [the Anglo-Saxon geara, clothing]. A general name for the rigging of any particular spar or sail; and in or out of gear implies anything being fit or unfit for use.

GLEN. An Anglo-Saxon term denoting a dale or deep valley; still in use for a ravine.

GOD. We retain the Anglo-Saxon word to designate the Almighty; signifying good, to do good, doing good, and to benefit; terms such as our classic borrowings cannot pretend to.

GRIP. The Anglo-Saxon grep. The handle of a sword; also a small ditch or drain. To hold, as “the anchor grips.” Also, a peculiar groove in rifled ordnance.

GUTTER [Anglo-Saxon géotan, to pour out or shed]. A ditch, sluice, or gote.

HACOT. From the Anglo-Saxon hacod, a large sort of pike.

HAVEN [Anglo-Saxon, hæfen]. A safe refuge from the violence of wind and sea; much the same as harbour, though of less importance. A good anchorage rather than place of perfect shelter. Milford Haven is an exception.

HAVEN-SCREAMER. The sea-gull, called hæfen by the Anglo-Saxons.

HEFT. The Anglo-Saxon hæft; the handle of a dirk, knife, or any edge-tool; also, the handle of an oar.

HELMY. Rainy [from an Anglo-Saxon phrase for rainy weather].

HERE-FARE [Anglo-Saxon]. An expedition; going to warfare.

HERRING. A common fish—the Clupea harengus; Anglo-Saxon hæring and hering.

HILL. In use with the Anglo-Saxons. An insulated rise of the ground, usually applied to heights below 1000 feet, yet higher than a hillock or hummock.

HOLD. The whole interior cavity of a ship, or all that part comprehended between the floor and the lower deck throughout her length.—The after-hold lies abaft the main-mast, and is usually set apart for the provisions in ships of war.—The fore-hold is situated about the fore-hatchway, in continuation with the main-hold, and serves the same purposes.—The main-hold is just before the main-mast, and generally contains the fresh water and beer for the use of the ship’s company.—To rummage the hold is to examine its contents.—To stow the hold is to arrange its contents in the most secure and commodious manner possible.—To trim the hold. Also, an Anglo-Saxon term for a fort, castle, or stronghold.—Hold is also generally understood of a ship with regard to the land or to another ship; hence we say, “Keep a good hold of the land,” or “Keep the land well aboard,” which are synonymous phrases, implying to keep near the land; when applied to a ship, we say, “She holds her own;” i.e. goes as fast as the other ship; holds her wind, or way.—To hold. To assemble for public business; as, to hold a court-martial, a survey, &c.—Hold! An authoritative way of separating combatants, according to the old military laws at tournaments, &c.; stand fast!

HOLT [from the Anglo-Saxon]. A peaked hill covered with a wood.

HORN-FISC. Anglo-Saxon for the sword-fish.

HOUND-FISH. The old Anglo-Saxon term for dog-fish—húnd-fisc.

HURST. Anglo-Saxon to express a wood.

HYTHE. A pier or wharf to lade or unlade wares at [from the Anglo-Saxon hyd, coast or haven].

I-L

ILAND. The Saxon ealand (See Island.)

KEEL. The lowest and principal timber of a ship, running fore and aft its whole length, and supporting the frame like the backbone in quadrupeds; it is usually first laid on the blocks in building, being the base of the superstructure. Accordingly, the stem and stern-posts are, in some measure, a continuation of the keel, and serve to connect the extremities of the sides by transoms, as the keel forms and unites the bottom by timbers. The keel is generally composed of several thick pieces placed lengthways, which, after being scarphed together, are bolted and clinched upon the upper side. In iron vessels the keel is formed of one or more plates of iron, having a concave curve, or limber channel, along its upper surface.—To give the keel, is to careen.—Keel formerly meant a vessel; so many “keels struck the sands.” Also, a low flat-bottomed vessel used on the Tyne to carry coals (21 tons 4 cwt.) down from Newcastle for loading the colliers; hence the latter are said to carry so many keels of coals. [Anglo-Saxon ceol, a small bark.]—False keel. A fir keel-piece bolted to the bottom of the keel, to assist stability and make a ship hold a better wind. It is temporary, being pinned by stake-bolts with spear-points; so when a vessel grounds, this frequently, being of fir or Canada elm, floats and comes up alongside.—Rabbets of the keel. The furrow, which is continued up stem and stern-post, into which the garboard and other streaks fay. The butts take into the gripe ahead, or after-deadwood and stern-post abaft.—Rank keel. A very deep keel, one calculated to keep the ship from rolling heavily.—Upon an even keel. The position of a ship when her keel is parallel to the plane of the horizon, so that she is equally deep in the water at both ends.

KEELS. An old British name for long vessels—formerly written ceol and cyulis. Verstegan informs us that the Saxons came over in three large ships, styled by themselves keeles.

KERS. An Anglo-Saxon word for water-cresses.

KNAP [from the Anglo-Saxon cnæp, a protuberance]. The top of a hill. Also, a blow or correction, as “you’ll knap it,” for some misdeed.

LADE. Anglo-Saxon lædan, to pour out. The mouth of a channel or drain. To lade a boat, is to throw water out.

LAGAN, or Lagam. Anglo-Saxon liggan. A term in derelict law for goods which are sunk, with a buoy attached, that they may be recovered. Also, things found at the bottom of the sea. Ponderous articles which sink with the ship in wreck.

LEAK [Anglo-Saxon leccinc]. A chink in the deck, sides, or bottom of a ship, through which the water gets into her hull. When a leak begins, a vessel is said to have sprung a leak.

LEWTH [from the Anglo-Saxon lywd]. A place of shelter from the wind.

LEX, or Leax. The Anglo-Saxon term for salmon.

LODESMEN. An Anglo-Saxon word for pilots.

M-O

MARSH [Anglo-Saxon mersc, a fen]. Low land often under water, and producing aquatic vegetation. Those levels near the sea coast are usually saturated with salt water.

MAST [Anglo-Saxon mæst, also meant chief or greatest]. A long cylindrical piece of timber elevated perpendicularly upon the keel of a ship, to which are attached the yards, the rigging, and the sails. It is either formed of one piece, and called a pole-mast, or composed of several pieces joined together and termed a made mast. A lower mast is fixed in the ship by sheers, and the foot or keel of it rests in a block of timber called the step, which is fixed upon the keelson.—Expending a mast, or carrying it away, is said, when it is broken by foul weather.—Fore-mast. That which stands near the stem, and is next in size to the main-mast.—Jury-mast.—Main-mast. The largest mast in a ship.—Mizen-mast. The smallest mast, standing between the main-mast and the stern.—Over-masted, or taunt-masted. The state of a ship whose masts are too tall or too heavy.—Rough-mast, or rough-tree. A spar fit for making a mast.—Springing a mast. When it is cracked horizontally in any place.—Top-mast. A top-mast is raised at the head or top of the lower-mast through a cap, and supported by the trestle-trees.—Topgallant-mast. A mast smaller than the preceding, raised and secured to its head in the same manner.—Royal-mast. A yet smaller mast, elevated through irons at the head of the topgallant-mast; but more generally the two are formed of one spar.—Under-masted or low-masted ships. Vessels whose masts are small and short for their size.—To mast a ship. The act of placing a ship’s masts.

MAST-ROPE [Anglo-Saxon mæst-ràp]. That which is used for sending masts up or down.

MERE. An Anglo-Saxon word still in use, sometimes meaning a lake, and generally the sea itself.

MEW [Anglo-Saxon mæw]. A name for the sea-gull.

MIST [Anglo-Saxon]. A thin vapour, between a fog and haze, and is generally wet.

MOUNT, or Mountain. An Anglo-Saxon term still in use, usually held to mean eminences above 1000 feet in height. In a fort it means the cavalier.

MOUTH [the Anglo-Saxon muda]. The embouchure opening of a port or outlet of a river, as Yarmouth, Tynemouth, Exmouth, &c.

NAME-BOOK. The Anglo-Saxon nom-bóc, a mustering list.

NORTH. From the Anglo-Saxon nord.

OAKUM [from the Anglo-Saxon æcumbe]. The state into which old ropes are reduced when they are untwisted and picked to pieces. It is principally used in caulking the seams, for stopping leaks, and for making into twice-laid ropes. Very well known in workhouses.—White Oakum. That which is formed from untarred ropes.

OVERWHELM. A comprehensive word derived from the Ang.-Saxon wylm, a wave. Thus the old song—

P-R

PORT. An old Anglo-Saxon word still in full use. It strictly means a place of resort for vessels, adjacent to an emporium of commerce, where cargoes are bought and sold, or laid up in warehouses, and where there are docks for shipping. It is not quite a synonym of harbour, since the latter does not imply traffic. Vessels hail from the port they have quitted, but they are compelled to have the name of the vessel and of the port to which they belong painted on the bow or stern.—Port is also in a legal sense a refuge more or less protected by points and headlands, marked out by limits, and may be resorted to as a place of safety, though there are many ports but rarely entered. The left side of the ship is called port, by admiralty order, in preference to larboard, as less mistakeable in sound for starboard.—To port the helm. So to move the tiller as to carry the rudder to the starboard side of the stern-post.—Bar-port. One which can only be entered when the tide rises sufficiently to afford depth over a bar; this in many cases only occurs at spring-tides.—Close-port. One within the body of a city, as that of Rhodes, Venice, Amsterdam, &c.—Free-port. One open and free of all duties for merchants of all nations to load and unload their vessels, as the ports of Genoa and Leghorn. Also, a term used for a total exemption of duties which any set of merchants enjoy, for goods imported into a state, or those exported of the growth of the country. Such was the privilege the English enjoyed for several years after their discovery of the port of Archangel, and which was taken from them on account of the regicide in 1648.

PUNT. An Anglo-Saxon term still in use for a flat-bottomed boat, used by fishermen, or for ballast lumps, &c.

ROPE. Is composed of hemp, hide, wire, or other stuff, spun into yarns and strands, which twisted together forms the desired cordage. The word is very old, being the actual representative of the Anglo-Saxon ráp.—To rope a sail. To sew the bolt-rope round its edges, to strengthen it and prevent it from rending.

ROTHER. This lineal descendant of the Anglo-Saxon róter is still in use for rudder.

ROVING COMMISSION. An authority granted by the Admiralty to a select officer in command of a vessel, to cruise wherever he may see fit. [From the Anglo-Saxon ròwen.]

RUDDER. The appendage attached by pintles and braces to the stern-post of a vessel, by which its course through the water is governed. It is formed of several pieces of timber, of which the main one is generally of oak, extending the whole length. Tiphys is said to have been its inventor. The Anglo-Saxon name was steor-roper.

RYNE. An Anglo-Saxon word still in use for a water-course, or streamlet which rises high with floods.

S-Z

SACK, To [from the Anglo-Saxon sæc]. To pillage a place which has been taken by storm.

SCONCE. A petty fort. Also, the head; whence Shakespeare’s pun in making Dromio talk of having his sconce ensconced. Also, the Anglo-Saxon for a dangerous candle-holder, made to let into the sides or posts in a ship’s hold. Also, sconce of the magazine, a close safe lantern.

SCOT, or Shot. Anglo-Saxon sceat. A share of anything; a contribution in fair proportion.

SCRAPER [from the Anglo-Saxon screope]. A small triangular iron instrument, having two or three sharp edges. It is used to scrape the ship’s side or decks after caulking, or to clean the top-masts, &c. This is usually followed by a varnish of turpentine, or a mixture of tar and oil, to protect the wood from the weather. Also, metaphorically, a cocked hat, whether shipped fore-and-aft or worn athwart-ships.

SCURRY. Perhaps from the Anglo-Saxon scur, a heavy shower, a sudden squall. It now means a hurried movement; it is more especially applied to seals or penguins taking to the water in fright.

SEAL [from the Anglo-Saxon seolh]. The well-known marine piscivorous animal.

SEAM. The sewing together of two edges of canvas, which should have about 110 stitches in every yard of length. Also, the identical Anglo-Saxon word for a horse-load of 8 bushels, and much looked to in carrying fresh fish from the coast. Also, the opening between the edges of the planks in the decks and sides of a ship; these are filled with a quantity of oakum and pitch, to prevent the entrance of water.

SETTLE. Now termed the stern-sheets [derived from the Anglo-Saxon settl, a seat].—To settle. To lower; also to sink, as “the deck has settled;” “we settled the land.” “Settle the main top-sail halliards,” i.e. ease them off a little, so as to lower the yard, as on shaking out a reef.

SHACKLE [from the Anglo-Saxon sceacul]. A span with two eyes and a bolt, attached to open links in a chain-cable, at every 15 fathoms; they are fitted with a movable bolt, so that the chain can there be separated or coupled, as circumstances require. Also, an iron loop-hooked bolt moving on a pin, used for fastening the lower-deck port-bars.

SHIFT. In ship-building, when one butt of a piece of timber or plank overlaunches the butt of another, without either being reduced in length, for the purpose of strength and stability.—To shift [thought to be from the Anglo-Saxon scyftan, to divide]. To change or alter the position of; as, to shift a sail, top-mast, or spar; to shift the helm, &c. Also, to change one’s clothes.

SHIP [from the Anglo-Saxon scip]. Any craft intended for the purposes of navigation; but in a nautical sense it is a general term for all large square-rigged vessels carrying three masts and a bowsprit—the masts being composed of a lower-mast, top-mast, and topgallant-mast, each of these being provided with tops and yards.—Flag-ship. The ship in which the admiral hoists his flag; whatever the rank of the commander be; all the lieutenants take rank before their class in other ships.—Line-of-battle ship. Carrying upwards of 74 guns.—Ship of war. One which, being duly commissioned under a commissioned officer by the admiralty, wears a pendant. The authority of a gunboat, no superior being present, is equal to that of an admiral.—Receiving ship. The port, guard, or admiral’s flag-ship, stationed at any place to receive volunteers, and bear them pro. tem. in readiness to join any ship of war which may want hands.—Store-ship. A vessel employed to carry stores, artillery, and provisions, for the use of a fleet, fortress, or Garrison.—Troop-ship. One appointed to carry troops, formerly called a transport.—Hospital-ship. A vessel fitted up to attend a fleet, and receive the sick and wounded. Scuttles are cut in the sides for ventilation. The sick are under the charge of an experienced surgeon, aided by a staff of assistant-surgeons, a proportional number of assistants, cook, baker, and nurses.—Merchant ship.—A vessel employed in commerce to carry commodities of various sorts from one port to another.—Private ship of war. —Slaver, or slave-ship. A vessel employed in carrying negro slaves.—To ship. To embark men or merchandise. It also implies to fix anything in its place, as “Ship the oars,” i.e. place them in their rowlocks; “Ship capstan-bars.” Also, to enter on board, or engage to join a ship.—To ship a sea. A wave breaking over all in a gale. Hence the old saying— “Sometimes we ship a sea,

Sometimes we see a ship.” To ship a swab. A colloquialism for mounting an epaulette, or receiving a commission.

SHIP-CRAFT. Nearly the same as the Anglo-Saxon scyp-cræft, an early word for navigation.

SHIPMAN [Anglo-Saxon scyp-mann]. The master of a barge, who in the days of Chaucer had but “litel Latin in his mawe,” and who, though “of nice conscience toke he no kepe,” was certainly a good fellow.

SHIP-STAR. The Anglo-Saxon scyp-steora, an early name for the pole-star, once of the utmost importance in navigation.

SHOOT-FINGER. This was a term in use with the Anglo-Saxons from its necessity in archery, and is now called the trigger-finger from its equal importance in modern fire-arms. The mutilation of this member was always a most punishable offence; for which the laws of King Alfred inflicted a penalty of fifteen shillings, which at that time probably was a sum beyond the bowman’s means.

SLADE [the Anglo-Saxon slæd]. A valley or open tract of country.

SMELT [Anglo-Saxon, smylt]. The fry of salmon, samlet, or Salmo eperlanus.

SNOOD [Anglo-Saxon, snod]. A short hair-line or wire to which hooks are fastened below the lead in angling. Or the link of hair uniting the hook and fishing-line.

SOUND [Anglo-Saxon, sund]. An arm of the sea over the whole extent of which soundings may be obtained, as on the coasts of Norway and America. Also, any deep bay formed and connected by reefs and sand-banks. On the shores of Scotland it means a narrow channel or strait. Also, the air-bladder of the cod, and generally the swimming-bladder or “soundes of any fysshes.” Also, a cuttle-fish.

SOUNDING-LINE. This line, with a plummet, is mentioned by Lucilius; and was the sund-gyrd of the Anglo-Saxons.

SPARTHE. An Anglo-Saxon term for a halbert or battle-axe.

SPELL. The period wherein one or more sailors are employed in particular duties demanding continuous exertion. Such are the spells to the hand-lead in sounding, to working the pumps, to look out on the mast-head, &c., and to steer the ship, which last is generally called the “trick at the wheel.” Spel-ian, Anglo-Saxon, “to supply another’s room.” Thus, Spell ho! is the call for relief.

SPRIT [Anglo-Saxon, spreotas]. A small boom which crosses the sail of a boat diagonally from the mast to the upper aftmost corner: the lower end of the sprit rests in a sort of becket called the snotter, which encircles the mast at that place. These sails are accordingly called sprit-sails. Also, in a sheer-hulk, a spur or spar for keeping the sheers out to the required distance, so that their head should plumb with the centre of the ship when taking out or putting in masts.

STADE. The Anglo-Saxon stæde, still in use. A station for ships. From stade is derived staith.

STAITH [Anglo-Saxon stæde]. An embankment on the river bank whence to load vessels. Also, a large wooden wharf, with a timber frame of either shoots or drops, according to circumstances.

STARBOARD. The opposite of larboard or port; the distinguishing term for the right side of a ship when looking forward [from the Anglo-Saxon stéora-bórd].

STEEP-TO. [Anglo-Saxon stéap.] Said of a bold shore, admitting of the largest vessels coming very close to the cliffs without touching the bottom.

STEERING [Anglo-Saxon stéoran]. The perfection of steering consists in a vigilant attention to the motion of the ship’s head, so as to check every deviation from the line of her course in the first instant of its commencement, and in applying as little of the power of the helm as possible, for the action of the rudder checks a ship’s speed.

STERE’S-MAN. A pilot or steerer, from the Anglo-Saxon stéora.

STORMS [from the Anglo-Saxon steorm]. Tempests, or gales of wind in nautic language, are of various kinds, and will be found under their respective designations. But that is a storm which reduces a ship to her storm staysails, or to her bare poles.

STRAND. A number of rope-yarns twisted together; one of the twists or divisions of which a rope is composed. The part which passes through to form the eye of a splice. Also, a sea-margin; the portion alternately left and covered by tides. Synonymous with beach. It is not altered from the original Anglo-Saxon.

STREAM. Anglo-Saxon for flowing water, meaning especially the middle or most rapid part of a tide or current.

STRING [Anglo-Saxon stræng]. In ship-building, a strake within side, constituting the highest range of planks in a ship’s ceiling, and it answers to the sheer-strake outside, to the scarphs of which it gives strength.

SWIM, To [from the Anglo-Saxon swymm]. To move along the surface of the water by means of the simultaneous movement of the hands and feet. With the Romans this useful art was an essential part of education.

SYKE [from the Anglo-Saxon sych]. A streamlet of water that flows in winter and dries up in summer.

TAKEL [Anglo-Saxon]. The arrows which used to be supplied to the fleet; the takill of Chaucer.

TALE [from Anglo-Saxon tael, number]. Taylor thus expressed it in 1630—

TAR [Anglo-Saxon tare]. A kind of turpentine which is drained from pines and fir-trees, and is used to preserve standing rigging, canvas, &c., from the effects of weather, by rendering them water-proof. Also, a perfect sailor; one who knows his duty thoroughly. (See Jack Tar.)—Coal or gas tar. A fluid extracted from coal during the operation of making gas, &c.; chiefly used on wood and iron, in the place of paint.

TARGET [Anglo-Saxon targe]. A leathern shield. A mark to aim at.

TAUT [from the Anglo-Saxon tought]. Tight.

THOLE, Thole-pin, or Thowel [from the Anglo-Saxon thol]. Certain pins in the gunwale of a boat, instead of the rowlock-poppets, and serving to retain the oars in position when pulling; generally there is only one pin to each oar, which is retained upon the pin by a grommet, or a cleat with a hole through it, nailed on the side of the oar. The principal use is to allow the oar, in case of action, suddenly to lie fore-and-aft over the side, and take care of itself. This was superseded by the swinging thowel, or metal crutch, in 1819, and by admiralty order at Portsmouth Yard in 1830.

TIMBER [Anglo-Saxon]. All large pieces of wood used in ship-building, as floor-timbers, cross-pieces, futtocks, frames, and the like (all which see).

TON, or Tun [from the Anglo-Saxon tunne]. In commerce, 20 cwt., or 2240 lbs., but in the cubical contents of a ship it is the weight of water equal to 2000 lbs., by the general standard for liquids. A tun of wine or oil contains 4 hogsheads. A ton or load of timber is a measure of 40 cubic feet in the rough, and of 50 when sawn: 42 cubic feet of articles equal one ton in shipment.

TONGUE [Anglo-Saxon tunga]. The long tapered end of one piece of timber made to fay into a scarph at the end of another piece, to gain length. Also, a low salient point of land. Also, a dangerous mass of ice projecting under water from an iceberg or floe, nearly horizontally; it was on one of these shelves that the Guardian frigate struck.

TOR. A high rock or peak: also a tower, thus retaining the same meaning it had, as torr, with the Anglo-Saxons.

TOTTY-LAND. Certain heights on the side of a hill [probably derived from the Anglo-Saxon totian, to elevate].

TOW-LINE [Anglo-Saxon toh-line]. A small hawser or warp used to move a ship from one part of a harbour or road to another by means of boats, steamers, kedges, &c.

TROUGH [from the Anglo-Saxon troh]. A small boat broad at both ends. Also, the hollow or interval between two waves, which resembles a broad and deep trench perpetually fluctuating. As the set of the sea is produced by the wind, the waves and the trough are at right angles with it; hence a ship rolls heaviest when she is in the trough of the sea.

TUG, To [from the Anglo-Saxon teogan, to pull]. It now signifies to hang on the oars, and get but little or nothing ahead.

WADE, To. An Anglo-Saxon word, meaning to pass through water without swimming. In the north, the sun was said to wade when covered by a dense atmosphere.

WAFT [said to be from the Anglo-Saxon weft], more correctly written wheft. It is any flag or ensign, stopped together at the head and middle portions, slightly rolled up lengthwise, and hoisted at different positions at the after-part of a ship. Thus, at the ensign-staff, it signifies that a man has fallen overboard; if no ensign-staff exists, then half-way up the peak. At the peak, it signifies a wish to speak; at the mast-head, recalls boats; or as the commander-in-chief or particular captain may direct.

WAR-SCOT.

A contribution for the supply of arms and armour, in the time of the Saxons.

WAVE [from the Anglo-Saxon wæg]. A volume of water rising in surges above the general level, and elevated in proportion to the wind.

WEATHER [from the Anglo-Saxon wæder, the temperature of the air]. The state of the atmosphere with regard to the degree of wind, to heat and cold, or to dryness and moisture, but particularly to the first. It is a word also applied to everything lying to windward of a particular situation, hence a ship is said to have the weather-gage of another when further to windward. Thus also, when a ship under sail presents either of her sides to the wind, it is then called the weather-side, and all the rigging situated thereon is distinguished by the same epithet. It is the opposite of lee. To weather anything is to go to windward of it. The land to windward, is a weather shore.

WEDGE [from the Anglo-Saxon wege]. A simple but effective mechanical force; a triangular solid on which a ship rests previous to launching. Many of the wedges used in the building and repairing of vessels are called sett-wedges.

WEEVIL [from the Anglo-Saxon wefl]. Curculio, a coleopterous insect which perforates and destroys biscuit, wood, &c.

WEIGH, To [from the Anglo-Saxon woeg]. To move or carry. Applied to heaving up the anchor of a ship about to sail, but also to the raising any great weight, as a sunken ship, &c.

WELKIN [from, the Anglo-Saxon, weal can]. The visible firmament. “One cheer more to make the welkin ring.”

WELL [from the Anglo-Saxon wyll]. A bulk-headed inclosure in the middle of a ship’s hold, defending the pumps from the bottom up to the lower deck from damage, by preventing the entrance of ballast or other obstructions, which would choke the boxes or valves in a short time, and render the pumps useless. By means of this inclosure the artificers may likewise more readily descend into the hold, to examine or repair the pumps, as occasion requires.

WESTWARD [Anglo-Saxon weste-wearde].—Westward-hoe. To the west! It was one of the cries of the Thames watermen.

WHITTLE [from the Anglo-Saxon hwytel]. A knife; also used for a sword, but contemptuously.—To whittle. To cut sticks.

WICK [Anglo-Saxon wyc]. A creek, bay, or village, by the side of a river.

WINCH [from the Anglo-Saxon wince]. A purchase formed by a shaft whose extremities rest in two channels placed horizontally or perpendicularly, and furnished with cranks, or clicks, and pauls. It is employed as a purchase by which a rope or tackle-fall may be more powerfully applied than when used singly. A small one with a fly-wheel is used for making ropes and spun-yarn. Also, a support to the windlass ends. Also, the name of long iron handles by which the chain-pumps are worked. Also, a small cylindrical machine attached to masts or bitts in vessels, for the purpose of hoisting anything out of the hold, warping, &c.

WIND [precisely the Anglo-Saxon word]. A stream or current of air which may be felt. The horizon being divided into 32 points, the wind which blows from any of them has an assignable name.

YARD [Anglo-Saxon gyrde]. A long cylindrical timber suspended upon the mast of a vessel to spread a sail. They are termed square, lateen, or lug: the first are suspended across the masts at right angles, and the two latter obliquely. The square yards taper from the middle, which is called the slings, towards the extremities, which are termed the yard-arms; and the distance between is divided by the artificers into quarters, called the first, second, third quarters, and yard-arms. The middle quarters are formed into eight sides, and each of the end parts is figured like the frustum of a cone: on the alternate sides of the octagon, in large spars, oak battens are brought on and hooped, so as to strengthen, and yet not greatly increase, the weight.—To brace the yards. To traverse them about the masts, so as to form greater or lesser angles with the ship’s length.—To square the yards.

YESTY [from the Anglo-Saxon gist]. A foaming breaking sea. Shakespeare in Macbeth gives great power to this state of the waters:— “Though the yesty waves

Confound, and swallow navigation up.”

YOUNGSTER, or Younker [an old term; from the Anglo-Saxon junker]. A volunteer of the first-class, and a general epithet for a stripling in the service.

Save

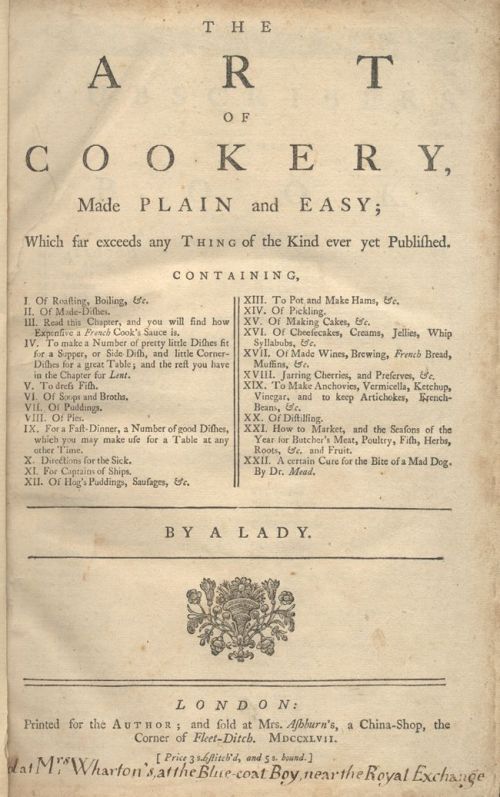

The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy was written in 1747 by Hannah Glasse (1708-1770) and played a dominant role in shaping the practices of domestic cooks in England and the American colonies for over one hundred years. It is an excellent reference for historical writers, reenactors, and living museums. Hannah wrote mostly for the “lower sort” as she called them, domestic servants who might not have had much exposure to various cooking techniques or ingredients before entering the service of a larger household. She wrote it in a simple language, and can come across at times quite condescending; her writing style, spelling variations (including capitalisation which was much like German, with all nouns capitalised), and punctuation are in themselves a fascinating look at the standard of printing and editing, and what was most likely “acceptable English” of the times (I dread to think what future generations might assume is the “standard” of our own times, based on the slipshod average of what is unleashed online…!). I’ve tried to leave Hannah’s work as-is, though sometimes the auto-correct sneaks by even the most diligent.

The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy was written in 1747 by Hannah Glasse (1708-1770) and played a dominant role in shaping the practices of domestic cooks in England and the American colonies for over one hundred years. It is an excellent reference for historical writers, reenactors, and living museums. Hannah wrote mostly for the “lower sort” as she called them, domestic servants who might not have had much exposure to various cooking techniques or ingredients before entering the service of a larger household. She wrote it in a simple language, and can come across at times quite condescending; her writing style, spelling variations (including capitalisation which was much like German, with all nouns capitalised), and punctuation are in themselves a fascinating look at the standard of printing and editing, and what was most likely “acceptable English” of the times (I dread to think what future generations might assume is the “standard” of our own times, based on the slipshod average of what is unleashed online…!). I’ve tried to leave Hannah’s work as-is, though sometimes the auto-correct sneaks by even the most diligent.