In researching for my novel, “The Cardinal“, I did a lot of research into the Viking Age of Scotland, Norway, and in modern-day Britain. The following is a snippet of the notes and thoughts I percolated over while studying into this amazing time in world history. Some of the speculations, such as the motivations behind the Lindisfarne attack, are my own, based on studies and extrapolation.

I think it’s impossible to do justice to any information about the Vikings; their existence, culture, language, mentality, and the effect of their actions have had repercussions that echo down through the ages. They gave names to countless cities throughout the world, and even entire regions: The Norse kingdom of Dublin (Old Norse for “Black Pool”) was a major centre of the Norse slave trade; Limerick, Wexford and Wicklow were other major ports of trade; Russia gets its name from them, and the list goes on and on. Had they not been so successful in the slave trade and conquest, entire regions of the earth would be populated differently, place names would be vastly different, and English would be a far poorer language than it is today.

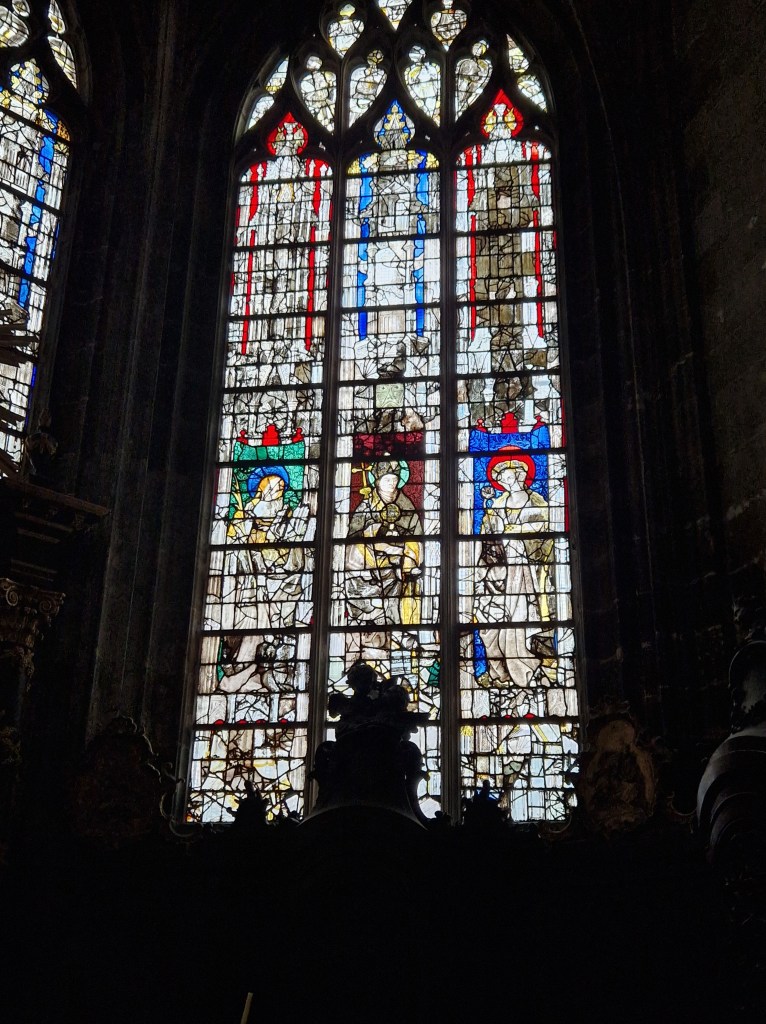

“A.D. 793. This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter.” (The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pg. 37)

This reference from The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, one of the most famous history books available in English, is a reference to what would become known as the beginning of the Viking Age, the attack on the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne. Firstly, I’d like to clarify a few points: “Viking” is a term that first came into being, in its present spelling, in 1840; it entered English through the Old Norse term “vikingr” in 1807. The Old Norse term meant “freebooter, pirate, sea-rover, or viking”, and the term “viking” meant “piracy, freebooting voyage.” The armies of what we would call Vikings were referred to by their contemporaries as Danes, and those who settled were known by the area they settled in, or visa-versa. Those who settled in the northeastern regions of Europe were called Rus by their Arabian and Constantinopolitan trading partners, perhaps related to the Indo-European root for “red”, referring to their hair colour, or – more likely – related to the Old Norse word of Roþrslandi, “the land of rowing,” in turn related to Old Norse roðr “steering oar,” from which we get such words as “rudder” and “row”.

Oh, and not a single Norse battle helmet with horns has ever been found.

I’d like to focus on a key point of the Lindisfarne episode, if one could refer so glibly to the slaughter of innocent monks and the beginning of the reign of terror that held the civilized world in constant fear for over two centuries: Yes, the Vikings were violent; their religion of violent gods and bloody sacrifices and rituals encouraged and cultivated it to a fine art. Yes, the Vikings were tradesmen, but they were also skilled pirates and raiders, that skill honed along their own home coasts for generations prior to their debut on the rest of the unsuspecting world. Yes, it was known that monasteries held items sacred to the Christian faith, that just happened to be exquisitely wrought works of art made of gold and jewels.

Gold was one enticement; but their primary trading good was human flesh; slaves. It was by far the most lucrative item, and readily had along any coast they chose; if too many died in the voyage they could always just get more before they docked at Constantinople, Dublin, or any other major trading port. So why did they slaughter the monks so mercilessly at Lindisfarne, when they would have gained more by taking them captive and either selling them as slaves or selling them for ransom? The answer might actually be found in Rome.

Charlemagne (ruled 768-814 AD) took up his father’s reigns and papal policies in 768 AD. From about 772 AD onwards, his primary occupation became the conversion to Christianity of the pagan Saxons along his northeastern frontier. It is very important to make a distinction between the modern expressions of the Christian faith and the institution of power mongers of past centuries; Christianity then had extremely little to do with the teachings of Christ and far more to do with political and military power, coercion, and acquisition of wealth through those powers; it was a political means to their own ends with the blessing of the most powerful politician in the history of the civilized world, the Pope. Without his blessing and benediction, a king had not only very little power, but was exposed to attack from anyone who had “holy permission” to exterminate heathens; joining the ranks of the Christian church took on the all-important definition of survival, and protection from the others in those ranks being free to attack you at their leisure.

In the year 772 AD, Charlemagne’s forces clashed with the Saxons and destroyed Irmensul, the Saxon’s most holy shrine and likely their version of the Yggdrasil, the Tree of the World, of Scandinavian mythology. In the Royal Frankish Annals of 775 AD, it was recorded that the king (Charlemagne) was so determined in his quest that he decided to persist until they were either defeated and forced to accept the papal authority (in the guise of “Christian faith”), or be entirely exterminated [Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, trans. Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers (Michigan 1972: 51)]. Charlemagne himself conducted a few mass “baptisms” to underscore the close identification of his military power with the Christian church.

“In 782 the Saxons rebelled again and defeated the Franks in the Süntel hills. Charlemagne’s response was the infamous massacre of Verden on the banks of the river Aller, just south of the neck of the Jutland peninsula. As many as 4,500 unarmed Saxon captives were forcibly baptised into the Church and then executed. Even this failed to end Saxon resistance and had to be followed up by a programme of transportations in 794 in which about 7,000 of them were forcibly resettled. Two further campaigns of forcible resettlement followed, in 797 and in 798…. Heathens were defined as less than fully human so that, under contemporary Frankish canon law, no penance was payable for the killing of one” [Ferguson, Robert (2009-11-05). The Hammer and the Cross: A New History of the Vikings (Kindle Locations 1048-1051). Penguin UK. Kindle Edition.]

The defining of a heathen as less than human was actually not a unique idea; Scandinavians were familiar with that notion from their own cultures, which defined slaves as less than human and therefore tradable goods; and if a freeman announced his intention of killing someone (anyone) it was not considered murder as the victim was given “fair” warning.

The more I learn about Charlemagne’s brutal policies toward what he considered sub-human pagans, the more I understand the reaction of retaliation toward the symbols of that so-called Christian faith, the monasteries and its inhabitants. They slaughtered, trampled, polluted, dug up altars, stole treasures, killed some, enslaved some, drove out others naked while heaping insults on them, and others they drowned in the sea. The latter was perhaps a tit-for-tat for those at Verden who were forcibly baptised and then killed.

Lindisfarne was merely the first major attack in Britain that was highly publicized (as chroniclers of history were usually monks, and those such as Alcuin knew the inhabitants of Lindisfarne personally), in what would become a 250-year reign of terror, violence, slavery, raping, pillaging, plundering and theft either by force or by Danegeld. But as in all good histories, it’s important to remember that hurt people hurt people; the perpetrator was at one time a victim. One might say that what goes around comes around. It’s no excuse or downplay of what happened there, which literally changed the course of the civilised world, but it perhaps gives a wider perspective on the Vikings of the times rather than just the vicious raiders portrayed in so many documentaries. And it is important to remember that Vikings did not equal Norsemen; the majority of Scandinavians were farmers and fishermen, living as peacefully as their times would allow, and even themselves victims to the occasional Viking raid.

Originally posted on History Undusted on 14 July 2013

Image Credit: Origin Unknown, Pinterest