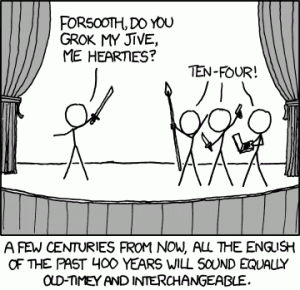

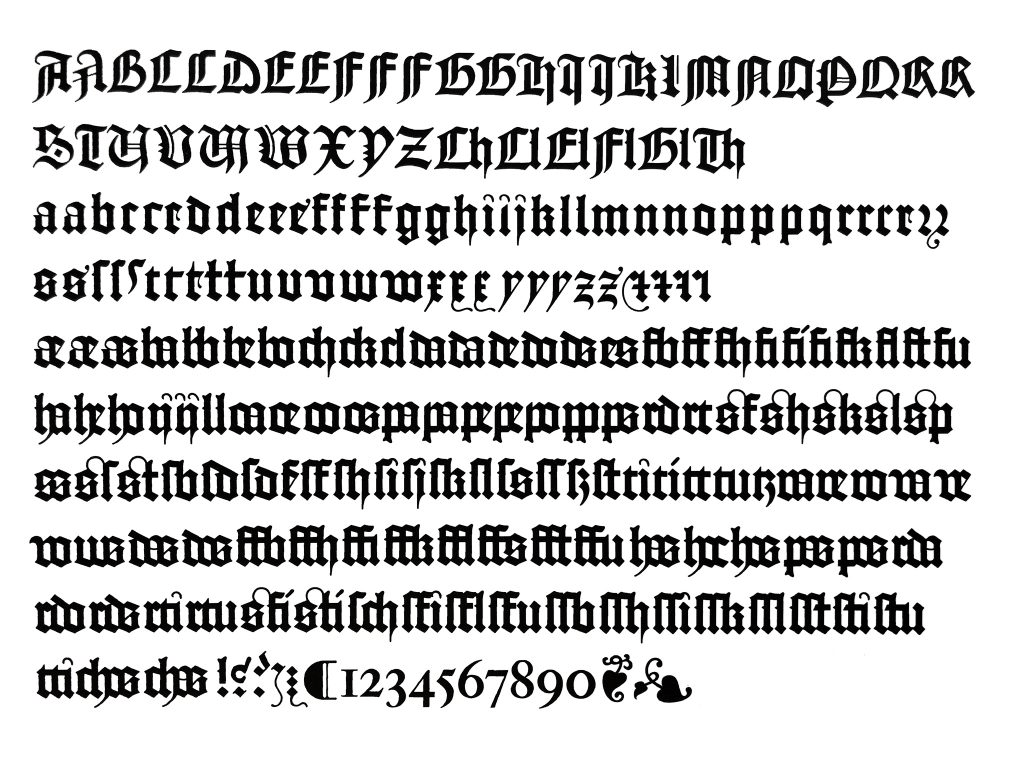

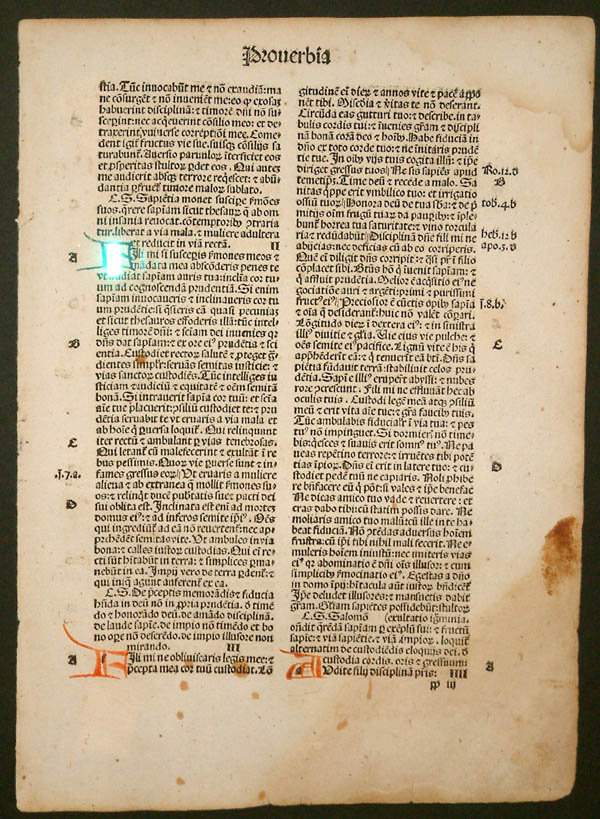

English is relatively young, as languages go. Like a sponge, it absorbs words and meanings from other languages, then squeezes them out in a similar (or widely different) form. In other words, English is a survivor; it has survived the attempts to destroy it by the Danish Vikings, the French (Normans, aka Vikings disguised as French), and the Germans. These historical encounters give me high hopes that it will survive the age of the Cell Phone. With each skirmish, it has come out stronger, more versatile and more flexible. When the Pilgrims packed up English and crated it off to the New World, it was locked, as it were, in a time capsule. British English absorbed a few bad habits from the French before they thought better of it and distanced themselves during the French Revolution, but in the meantime, contentious pronunciation differences to that time-capsule relative over the Pond had crept in and persist to this day. One example: The American pronunciation of schedule (/skedju(e)l/) is from the original Greek pronunciation, which was used in Britain for onk-years until they took on the fancier French-ified pronunciation of /shedju(e)l/. For a fascinating glimpse into how Modern English was formed, William Caxton (~1422-~1491) is your man.

While English pilled through the pockets of invaders stealing loose grammar, we also lost a few words along the way: Some words are known to us in one form but not the other, while other words have been lost altogether due to a more convenient absorption or form arising. You know of disgruntled (adj.), but what about gruntle (v.) or disgruntle (v.)? And dis– in this particular case is not used to form the antonym of gruntle, but means exceedingly gruntled. And I don’t know about you, but conject as a verb makes more sense than “conjecture” to me. And shall we vote to bring back “Oliphant,” as J.R.R. Tolkien saved it from extinction through his use of it in Lord of the Rings? What about pash (n.), contex (v.), or spelunk (n.)? We know of fiddle-faddle, but what about plain ol’ “faddle” (to trifle)? Some, admittedly, are not missed; toforan is better served with heretofore, in my humble opinion (IMHO). Needsways is a Scottish word, obsolete in England and America perhaps, but alive and well north of the Border. There are some deliciously eccentric words which deserve resuscitation, such as loblolly, bric-a-brac, sulter, pill (v., to plunder, pillage – ought to come in handy, that), quib, bugbear, uptake (as a verb), wist (intent), or sluggy. If Sir Walter Scott can save words such as doff and don from extinction, so can we.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about the word archaism, it means “retention of what is old and obsolete.” So twinge your language to include these mobile words and their meanings, and revelate your intelligence! And if you’re curious, yes, Grammarly and spellcheck were going batship crazy with this post!😎

Who’s Who in Quotes: Will Rogers

Will Rogers is one of those larger-than-life characters who seemed to have had his fingers in every pie imaginable: Born in November 1879 as a Cherokee Nation citizen in the Indian Territory now known as Oklahoma, he was the youngest of eight siblings, only three of whom survived into adulthood. His mother died when he was just ten years old. By the time he was 20, he’d begun appearing in rodeos, and in 1902 at the age of 22, he and a friend moved to Argentina to find work as gauchos (a skilled horseman, hired by ranchers in many South American countries). When their adventure failed, and they’d lost all their money, Will couldn’t bear to ask for money from home, so he took a boat to South Africa, where he was hired as a ranch hand. His career as a trick roper began there, as he joined the Texas Jack’s Wild West Circus. From there, armed with a letter of reference from Texas Jack, he moved to Australia and joined the Wirth Brothers Circus as a rider and trick roper. By 1904, he’d returned to the States and performed in the St. Louis World’s Fair, then began using his riding and roping skills in the Vaudeville circuits; he was often billed as The Cherokee Kid. His natural humour hit a chord with audiences, who loved his frontier twang of an accent coupled with his off-the-cuff wit and commentary on current events; he built his later career around that talent.

In 1908, he married Betty Blake, and they had four children; three survived into adulthood, all of whom went on to have careers in the public eye in one way or another.

By 1916, Rogers was a featured star in Ziegfeld’s Follies on Broadway; from there he branched off into silent films; at that time, most films were made in or around New York, which allowed him to continue performing on Broadway. The New York Times syndicated his weekly newspaper column, “Will Rogers Says”, from 1922 to 1935; he also wrote for The Saturday Evening Post; this progressed into books – over 30 of them. He also hosted a radio program, telling jokes and discussing current events with his simple, disarming humour.

Click here to see a short, 3-minute video showcasing some of his amazing rope tricks.

He was an avid supporter of the aviation industry, and he took many opportunities to fly to his various engagements. In 1926, while touring Europe, he saw how much more advanced the commercial services were there in comparison to the States; his newspaper columns often emphasized the safety and speed of travel aeroplanes offered, which helped shape public opinion about the new mode of transport.

In 1935, Wiley Post, a famous aviator of his time, proposed flying from the West Coast to Russia to find a mail-and-passenger air route, and Rogers asked to go with him in order to find new material for his newspaper columns. Post’s plane was modified for the long flight, and floats were added for landing on water. On 15 August, they took off from Fairbanks, Alaska, for Point Barrow, a headland on the Arctic coast. Bad weather hindered their ability to calculate their position, and, after landing in a lagoon to ask directions and taking off again, the engine failed at low altitude and plunged into the lagoon, killing both men. Rogers was 55.

In such a short life, he left a huge legacy in many fields of entertainment and helped shape public perspectives on politics and civil responsibility. He was a household name in the early 20th Century and a trusted voice during the Great Depression, identifying with the struggles of the average American and holding a mirror to politics with his witty satire.

Here are a few of his famous quotes:

2 Comments

Filed under History, History Undusted, Humanity Highlights, Quotes, Snapshots in History, YouTube Link

Tagged as Alaska, Australia, Aviation, Broadway, Cherokee Nation, Circus, Entertainment, Gauchos, Great Depression, Indian Territory, New York, New York Times, Oklahoma, Politics, Quotes, Satire, Saturday Evening Post, Social Commentary, The Cherokee Kid, Trick Roper, Vaudville, Who's Who in Quotes, Will Rogers, Ziegfeld's Follies