I recently watched the film “Emma”, with Gwyneth Paltrow and Jeremy Northam; as the proposal scene was playing, I noticed her earring and wondered if that was historically accurate – did they have pierced earrings in England at that time (the early 1800s)? I’m not into fashion (that’s an understatement – I’m very pragmatic when it comes to clothes!), but the historical aspect fascinated me enough to look into the matter.

While we have probably all heard of “Girl with a Pearl Earring”, painted ~1665 by Johannes Vermeer (doubts have been raised as to whether it is actually pearl or rather polished tin or coque de perle, given the reflective qualities and size, but that’s another issue), it is a Dutch painting from the 17th century and thus doesn’t answer my question. My interest lies more in the 1700s (18th Century) of Britain, and so I began researching 18th C. English portraits.

I discovered that, while there are many portraits with earrings displayed, there are far more without. So it would have been possible, but was by no means as common as it is today. Also, sometimes the current hairstyle hid the ears, such as that of the 1770s and 1780s, or perhaps their ears were hidden by the custom of married women wearing mob caps, even beneath other “public” hats.

Typical 1780s hairstyle; such a style would have either hidden earrings or made them obsolete.

A married woman wearing a mob cap under her bonnet (though from the black cape and hat combined with a white dress, she may be at the end of a period of mourning, wearing “half weeds”). Mrs Lewis Thomas Watson (Mary Elizabeth Milles, 1767–1818) by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1789

The portraits do not reveal whether or not they were merely clip-on earrings or studs, though ear piercing has been around for centuries, varying in intensity and use from culture to culture (some for religious purposes, some for ownership such as slave earrings, and others were status symbols for royalty or nobility). I’ve found many portraits from Europe as a whole, between the 16th and 19th centuries which portray women wearing earrings; here are a few, with their details:

1761, by Joshua Reynolds: Lady Elizabeth Keppel. Note that the Indian woman is also wearing an earring(s), and a rope of pearls; I don’t know whether she is portrayed as a servant or merely inferior in rank, due to her placement in the portrait…

Genevieve-Sophie le Coulteux du Molay, 1788 by Elisabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun. Though this is a French portrait by subject & painter, it is from the period in question and displays a hoop earring, as well as the hairstyle common in this period in England as well.

Turkish Dress, c1776 Portrait of a Woman, possibly Miss Hill

A young woman in powder blue, ca. 1777

Thomas Gainsborough, 1727-1788 London, Portrait of Lady Anne Furye, née Greenly

Based on History Undusted Original Post, June 2015

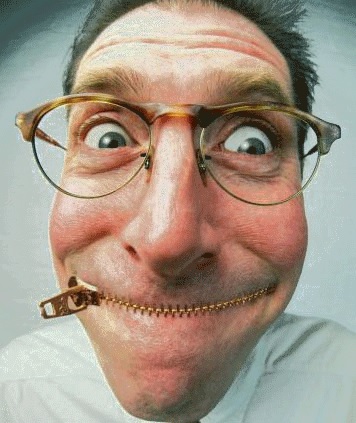

A zipper is something one rarely thinks about until it breaks. It’s something we use every day, from trousers to jackets to purses to zip-lock bags. Yet the actual modern zipper has only been around 101 years! The idea began forming as a practical design in 1851 in the mind of Elias Howe, who patented an “Automatic Continuous Clothing Closure” (no wonder that name never caught on). He was not a marketing whiz, and the idea petered out. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, a device designed by Whitcomb Judson was launched but wasn’t very practical, and again, it failed to take off commercially. In 1906, a Swedish-American electrical engineer by the name of Gideon Sundback was hired by (and married into) the Fastener Manufacturing and Machine Company (Meadville, PA), and became the head designer. By December 1913, he’d improved the fastener into what we would recognize as the modern zipper, and the patent for the “Separable Fastener” was issued in 1917. In March of that year, a Swiss inventor, Mathieu Burri, improved the design with a lock-in system added to the end of the row of teeth, but because of patent conflicts, his version never made it to production.

A zipper is something one rarely thinks about until it breaks. It’s something we use every day, from trousers to jackets to purses to zip-lock bags. Yet the actual modern zipper has only been around 101 years! The idea began forming as a practical design in 1851 in the mind of Elias Howe, who patented an “Automatic Continuous Clothing Closure” (no wonder that name never caught on). He was not a marketing whiz, and the idea petered out. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, a device designed by Whitcomb Judson was launched but wasn’t very practical, and again, it failed to take off commercially. In 1906, a Swedish-American electrical engineer by the name of Gideon Sundback was hired by (and married into) the Fastener Manufacturing and Machine Company (Meadville, PA), and became the head designer. By December 1913, he’d improved the fastener into what we would recognize as the modern zipper, and the patent for the “Separable Fastener” was issued in 1917. In March of that year, a Swiss inventor, Mathieu Burri, improved the design with a lock-in system added to the end of the row of teeth, but because of patent conflicts, his version never made it to production.

The word shilling most likely comes from a Teutonic word, skel, to resound or ring, or from skel (also skil), meaning to divide. The Anglo-Saxon poem “Widsith” tells us …”þær me Gotena cyninggodedohte; se me beag forgeaf, burgwarenafruma, on þam siexhund wæs smætes goldes, gescyred sceatta scillingrime...” “There the king of the Goths granted me treasure: the king of the city gave me a torc made from pure gold coins, worth six hundred pence.” Another translation says that the gold was an armlet, “scored” and reckoned in shilling. The “scoring” may refer to an ancient payment method also known as “hack” – they would literally hack off a chunk of silver or gold jewellery to purchase goods, services and land, and the scoring may have been pre-scored gold to make it easier to break in even increments, or “divisions”. From at least the times of the Saxons, shilling was an accounting term, a “benchmark” value to calculate the values of goods, livestock and property, but did not actually become a coin until the reign of Henry VII in the 1500s, then known as a testoon. The testoon’s name and design were most likely inspired by the Duke of Milan’s testone.

The word shilling most likely comes from a Teutonic word, skel, to resound or ring, or from skel (also skil), meaning to divide. The Anglo-Saxon poem “Widsith” tells us …”þær me Gotena cyninggodedohte; se me beag forgeaf, burgwarenafruma, on þam siexhund wæs smætes goldes, gescyred sceatta scillingrime...” “There the king of the Goths granted me treasure: the king of the city gave me a torc made from pure gold coins, worth six hundred pence.” Another translation says that the gold was an armlet, “scored” and reckoned in shilling. The “scoring” may refer to an ancient payment method also known as “hack” – they would literally hack off a chunk of silver or gold jewellery to purchase goods, services and land, and the scoring may have been pre-scored gold to make it easier to break in even increments, or “divisions”. From at least the times of the Saxons, shilling was an accounting term, a “benchmark” value to calculate the values of goods, livestock and property, but did not actually become a coin until the reign of Henry VII in the 1500s, then known as a testoon. The testoon’s name and design were most likely inspired by the Duke of Milan’s testone.