You know how your brain fires off random thoughts as you fall to sleep, or combines odds-bods into dreams forgotten as soon as you wake up? For some reason, 10-4 popped into my head in those moments last night. It sent me down the rabbit hole I now present: The history of the CB radio.

The often-forgotten or overlooked inventor of the Citizen’s Band (CB) radio system, along with inventions such as a patented version of the walkie-talkie (originally invented by the Englishman Donald Hings), the telephone pager, and the cordless telephone – all precursors to today’s cell phones, was Al Gross (1918-2000): Born in Toronto, Canada, he grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. The son of Romanian-Jewish immigrants, his love for electronics was sparked when, at the age of nine, he was travelling by steamboat on Lake Erie; he explored the ship and ended up in the radio transmissions room, where the operator let him listen in. Eventually, he turned the family’s basement into a radio station built from scraps. During his higher studies, he experimented with ways to use radio frequencies.

During World War 2, he had some involvement with developing a two-way VHF air-to-ground communications system for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, known as the Joan-Eleanor system, and after the war, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allocated a few frequencies for the Citizens’ Radio Service Frequency Band, in 1946. Gross saw the potential and founded the Gross Electronics Co. to produce two-way communications systems to make use of these frequencies; his firm was the first to receive FCC approval in 1948. For more about his other inventions, just follow the link on his name above. For now, let’s focus on the CB:

The CB radio became an international hit back before cell phones and computers became a thing (despite the prevalence of cell phones, CBs are still around; truckers still communicate about road conditions, etc. Its usage was also revived by the Covid lockdown, when people began reaching out to meet and talk to others outside of their own four walls). It was, and is, a way to communicate with others long-distance from home or on the go.

My dad was always interested in the latest technological gadgets; in the mid-70s, we got a laserdisc player, the precursor of CDs, and DVD/Blu-Ray players. I remember watching films like Logan’s Run and Heaven Can Wait on that format. Laserdiscs never really took off, and only about 2% of US households had one (it became more popular in Japan at the time). Around that time, we also got a CB radio in our VW van. My dad had a chart with all of the CB slang words and codes, and I memorised it, fascinated by the lingo. On long road trips, I would get on the CB and chat with truck drivers. My handle (nickname) was Spider-Fingers, as I liked spiders and had long fingers (long fingers has the connotation of thief, so I didn’t want to use that!). Here is just the tip of the iceberg, a smattering of the codes and slangs used by CB radio enthusiasts, truckers and handymen:

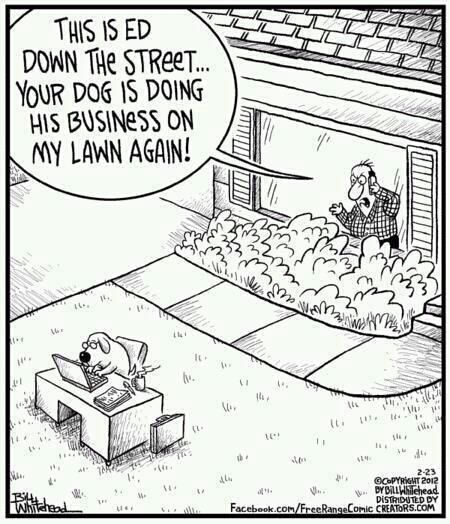

There were dozens of slang terms for law enforcement officers: Bear (police officer); bear trap (speed trap, radar trap) taking pictures, also called a Kojak With A Kodak; bear bait (an erratic or speeding driver); bear with ears (listening to CB traffic); bear in the air/flying doughnut/Spy in the sky (helicopter radar traps), baby bear (rookie), fox in the henhouse/Smokey in a plain wrapper (policemen in unmarked vehicles); honey bear, mamma bear or Miss Piggy (slangs for female police officers); Brush Your Teeth And Comb Your Hair (a law enforcement vehicle is radaring vehicles – as if preparing for an official photo). A Driving Award was a speeding ticket. To wish someone Shiny side up meant that you wished them safe travels (keeping the vehicle upright).

There were slang terms for objects or events, such as Bambi, meaning that there was wildlife near the road and to take precautions; a crotch rocket was a fast motorcycle; double-nickels was a 55-mph speed limit area; a fighter pilot was an erratic driver who switched lanes frequently, while a gear jammer was someone who sped up and slowed down frequently; Alabama chrome was duct tape; an alligator/gator was a piece of blown tire on the highway, as it looked in the distance like a gator sunbathing. Convoys had front doors and back doors – the front or back truck in the group that would keep an eye open for bear traps. Motion lotion was fuel; the hammer lane was the fast lane (hammer was the gas pedal, and to hammer down was to drive full-speed). Break/breaker: Informing other CB users that one wanted to start transmission on a channel; a handle might be introduced, or requested if someone was looking for a CB friend. “Breaker, this is Spider-Fingers, over.” Asking for a comeback meant that you couldn’t hear the last transmission or wanted the other driver to talk. Break check meant traffic congestion ahead, slow down. A Bumper Sticker/hitchhiker is a vehicle that is tailgating another vehicle.

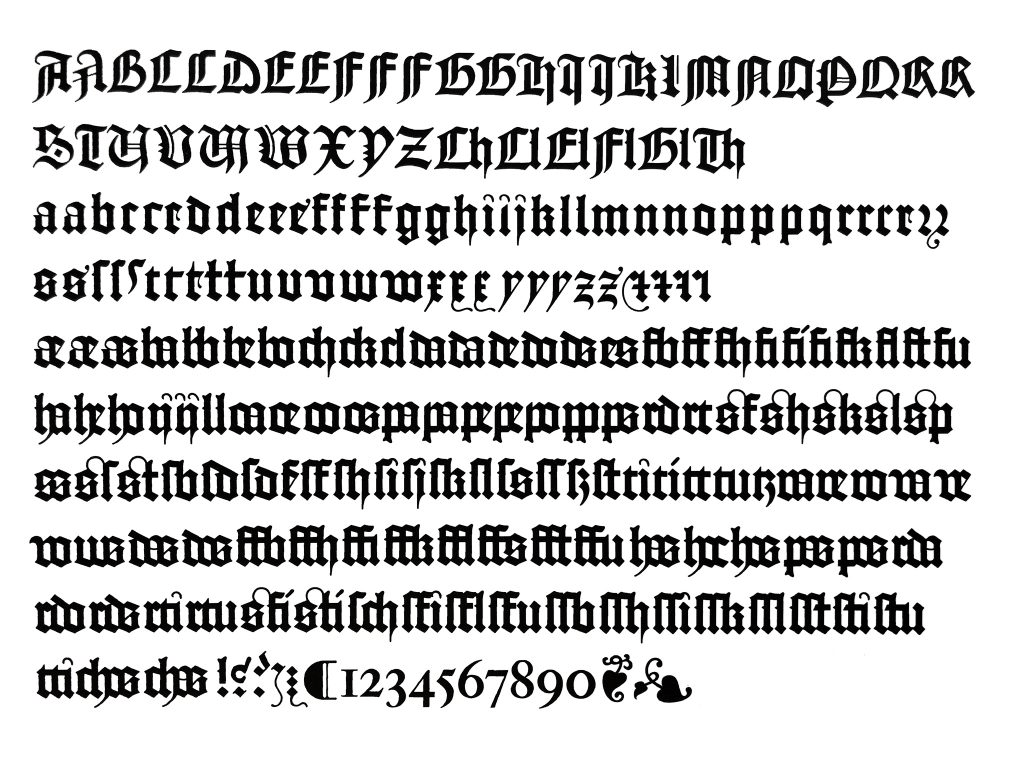

Aside from hundreds of slang terms, there was a whole list of codes (I guess you could say that the codes were the precursors of emojis!):

10-4: Agreed, understood, acknowledged

4-10: The opposite – asking for agreement or if a transmission was received.

10-6: Busy, stand by

10-7: Signing off

10-10: Transmission completed, standing by (you’ll be listening)

10-20: Location – What’s your (10-)20? Home-20 was asking for a driver’s home location/base.

10-33: Emergency traffic, clear the channel. CB code for Mayday for trucks and police cars.

10-42: Accident on the road

3s and 8s: Well wishes to a fellow driver. Borrowed from amateur ham radio codes “73” (best regards) and “88” (hugs and kisses).

The lists go on and on! I love the dry sense of humour reflected in the slang, and I think our everyday language could be a bit livelier if we included a few phrases that looked at things from a different perspective. Everyone could do with more 3s and 8s, 4-10?

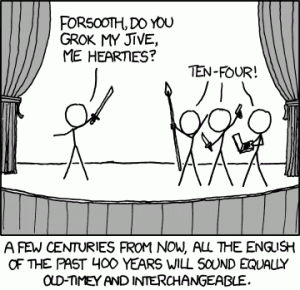

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.

Every generation creates new ones, because a parent’s euphemism becomes the general term which is then too close to the original meaning, and so the children get creative with words, and so on. There are a few euphemisms that have remained unchanged over centuries, such as passed away, which came into English from the French “passer” (to pass) in the 10th century; others shift gradually, such as the word “nice”: When it first entered English from the French in the 13th century, it meant foolish, ignorant, frivolous or senseless. It graduated to mean precise or careful [in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion”, Anne Elliot is speaking with her cousin about good society; Mr Elliot reponds, “Good company requires only birth, education, and manners, and with regard to education is not very nice.” Austen also reflects the next semantic change in meaning (which began to develop in the late 1760s): Within “Persuasion”, there are several instances of “nice” also meaning agreeable or delightful (as in the nice pavement of Bath).]. As with nice, the side-stepping manoeuvres of polite society’s language shift over time, giving us a wide variety of colourful options to choose from.